The fall of the Soviet Union and Fukuyama’s declaration of liberal capitalism as The End of History had profound and multifaceted impact upon our culture industries. Generation X — that relatively brief grouping of humans that were born in the late seventies and came of age in the nineties — experienced unprecedented economic boom times. The most upwardly mobile generation in history, Gen X Americans wield more spending power than boomers and millennials combined. The obscene financial success resulted in a palpable apathy towards radical politics – what is there to protest when there’s this much cocaine, anyways? – and an embrace of capitalism and “the mainstream” atypical of generational youth movements: “No one really knew what we were,” writes NY Times cultural critic Alex Williams on his hard-to-define generation. “But apparently someone knew what we weren’t: dreamers, revolutionaries, world-changers.”

Radical subculture largely died in the 1990s, swallowed whole by private equity and immediately regurgitated as commerce; grunge was being hailed as the return of punk rock for six months before Marc Jacobs turned it into a mainstream fashion statement for a Perry Ellis show in 1992. This rapid and hyper marketization of subculture is commonplace now – after all, the most avant-garde art and music is now being seen and heard at the fucking RED BULL Music Academy – but marked a rapid shift in political and cultural economy back then. Even in the 1980s there was still a clear border separating the mainstream and the underground of cultural production. That border was decimated once the Cold War had officially ended.

Perry Ellis Ready-to-Wear 1993

As commerce ravenously devoured all culture in its sight throughout the‘90s, some artists embraced their new roles as celebrities: Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons and other artists basked in the decadent artifice of celebrity and luxury lifestyle. Koons, perhaps more interestingly so than Hirst, embraced this progression of culture that would allow him to conceptualize art making as new form of product manufacturing. There was no deeper meaning to his art; it was the creative object as a pure commodity. What has made Koons enduringly relevant is the self-awareness he displays about his place in the art world. He makes art for the market, he understands the market. He literally worked in finance in the eighties to bankroll his burgeoning art career. “Jeff Koons embraces the capitalistic component of the art market without hypocrisy,” says art historian Robert-Pincus Witten. “He recognizes that works of art in a capitalist market are reduced to the condition of commodities. He short circuits the process, beginning with the commodity.” This understanding and acceptance of what the art market is, this embracing of the extravagantly privatized realties of liquid modernism, lends Koons more credibility than the artist who resists the economy and attempts to hold art as sacred. Koons is the artist as manipulator of markets.

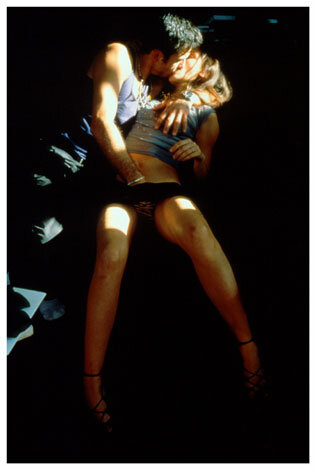

Meanwhile, other artists took refuge from the rampant corporatization of culture by inhabiting whatever was left of sub-cultural terrain. Nan Goldin, for instance, used photography to shine a spotlight on the “freaks” on society’s fringes. Her subjects were debauched angels, decadently pure of the corrupting forces of capital. Musicians took a similar tact. The rise of subterranean music scenes; noise, house, techno, and otherwise; created independent industries out of thriving subcultural movements. But even these artists weren’t immune to the voraciously cannibalistic hunger of neoliberal capitalism. Goldin’s photos are sold for millions to oligarchs and even the most outré of electronic music producers play festivals branded by Amazon, or worse.

Jeff Koons ‘Inflatable Pig Costume’

.

Nan Goldin ‘Joana and Aurelle Making Out in an Apartment’

No one better represents the dilemma of the “nineties Rimbaud” — a fiercely free-spirited poetic David against an all-encompassing industrial Goliath — better than Kurt Cobain.

Cobain, both brilliant and naive, came out of the independent subcultures of eighties punk rock. His sensibility was geared towards punk sleaze and the freedom of noise, but he also shouldered the burden of being a gifted writer of pop songs. His music was perfect for the commodification of punk, allowing MTV and its corporate sponsors to sell the revolution back to the more idiosyncratically-minded youth that had previously eluded them. His inability to reconcile being both a creator of art and a churner of product killed him. “Cobain knew he was just another piece of spectacle,” wrote Mark Fisher in Capitalist Realism. “That nothing runs better on MTV than a protest against MTV.”

Kurt Cobain

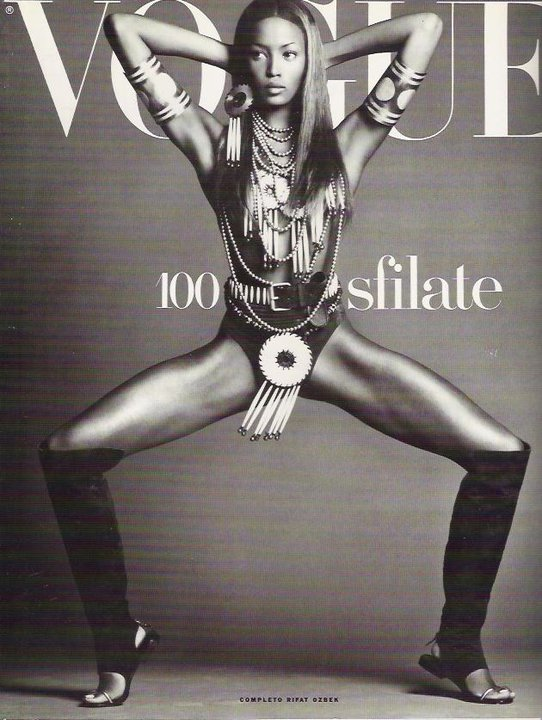

Perhaps in the most healthy-minded and rational position one can take as an artist operating within late capitalism, other artists of the Z generation decided to work within the confines of pre-corporatized mediums. As a result, commercial art experienced an explosion of creativity throughout the decade. Fashion photography became a repository of stylistic innovation: Steven Meisel, Juergen Teller, Corinne Day and others shunned self-serious fine art photographers and exploited the fashion image as a zone of unbridled fantasy and libidinal excess: “While much of fine art has succumbed to the ‘passion for the real,’” wrote Fisher in his essay on Meisel, “High fashion remains the last redoubt of Appearance and Fantasy.”

Naomi Campbell by Steven Meisel for Vogue

Perhaps no artists were more emblematic of the nineties’ collision of commerce and unparalleled expressivity than music video directors. In his text Paradoxes of Pastiche: Spike Jonze, Hype Williams, and the Race of the Postmodern Auteur, cultural critic Roger Beebe notes that it was in the early nineties that MTV added the director’s credit to its music video labels, effectively allowing video directors to transition from being known as hired hands to being respected as a new and distinctly postmodern auteur of the coke and money-addled generation of disaffection.

Bjork by Juergen Teller

MTV was at the height of its cultural caché, and because it was the popular music that was the actual draw for the network’s viewers, video directors were emboldened to create images that were often transgressive, intrepid, shocking and undeniably innovative. Some of these filmmakers — like David Fincher, who made his bones directing Madonna videos, or Spike Jonze, who made iconic videos for the likes of Beastie Boys and Sonic Youth — used their careers as launching pads towards Hollywood cinema. Others, due to either lack of ambition or absence of circumstance, made the music video their primary artistic form. British artist and filmmaker Chris Cunningham, for instance, is widely celebrated for directing videos that blended nightmarish, Francis Bacon-esque corporeal angst with Baudrillardian postmodern cyberpunk theory for Aphex Twin and others. Only the most conservative of art critics couldn’t find at least some merit within these obscene clips of manifested uncanny valley.

Aphex Twin ‘Windowlicker’ video, directed by Chris Cunningham

Only one filmmaker, however, was capable of stretching out the music video style that he pioneered over the course of an entire 90-minute feature film, manifesting a new cinematic form in the process. The Queens-born king of the hip-hop golden age’s maximalist visual style Hype Williams has one feature to his credit: the DMX and Nas-starring 1998 phantasmagoric, psychedelic gangster odyssey Belly. Belly is one of the purest expressions of Generation X art: all artifice, all seduction, all style. In his pioneering of this new form, Williams effectively created an artistic style that simly could not be replicated. Thus, Belly is less a work of cinema that an embodiment of pure zeitgeist.

Though it was almost universally panned upon its release, Belly has developed a passionate cult following, which shouldn’t surprise: it’s basically designed to invite a cult following. Its narrative is sparse, relying almost completely on seductive and enveloping visual style. Williams posited the journey of the drug dealer as a transcendental labyrinth into the heart of corruption itself. And though Williams may have had a vasty less impressive career in feature films than some of his contemporaries — he certainly hasn’t gone on to David Fincher-like success and definitely hasn’t made any masterpieces on the level that, say, Jonathan Glazer has with both Sexy Beast and Under the Skin — he managed to accomplish something with his chosen medium that no one else has been able to. With Belly, he brought the music video format to its absolute apex, and with that achievement, birthed a whole new genre of cinema.

Belly

When Hype Williams rose to prominence as a hip-hop video director – his first directorial credit was a cut for female rap duo BWP’s 1992 single “We Want Money” – rap music was experiencing a period of both unparalleled artistic innovation and cultural relevance. Similar to rock music in the 1970s, hip-hop in the 1990s was splintering into different sub-genres, flooding every sector of the music industry, and making billions of dollars. Rap stars — with their masterfully crafted public personas and transgressive sensibilities — quickly outpaced their rockstar counterparts in terms of recognizability, influence, and power.

Hype Williams’ uncanny genius was in his ability to craft videos that captured the essences of the artists he worked with, while still staying true to a singularly postmodern, afro-futurist and surrealist vision. Through Hype Williams’ hyperactive creativity, the “rap video continued to develop into something more eccentric, more colorful, more lavish, just plain more,” says film critic Nick Pinkerton. His videos were some of the most expensive of the nineties, sparing no expense in his vision of hip-hop as pop culture’s most radical and visionary force. His videos are full of light, of movement, of libidinal desire, of vibrant performativity. He understood who these artists were, what their places were in the culture, and how to express that through his own forceful vision.

Jay-Z ‘Big Pimpin’ music video, directed by Hype Williams

Consider two different videos from Williams’ biggest year, 1997, when Williams’ in-demand status was at its peak. ‘97 was Missy Elliot’s introduction to the world when she released her stunning Timbaland-produced debut masterpiece Supa Dupa Fly. Though Elliot is unfortunately overlooked as a legacy hip-hop act, she had a titanic influence on popular music, fashion and art. Unashamedly large and most-often donning vibrant sportswear, Elliot’s music is shamefully ignored for “how experimental it was,” says music writer Leah Sinclair. “She embraced house music on the Basement Jaxx remix ‘For My People’, and brought a Bhangra influence to ‘Get Ur Freak On’. She’s never been scared to engage with different musical styles.” Williams had the first stab at bringing Elliot’s energetic hybrid of R&B, rap, world music, and house to life, directing the video for Elliot’s Ann Peebles-sampling debut single “The Rain.”

In the video, Elliot wears a now-iconic trash bag jumpsuit with futuristic sunglasses and a cyborgian helmet, dancing in front of the camera captured in wide-angle. Enjoying all of Williams’ trademark cinematographic flourishes — the Fisheye lens distorting the camera view around the central focus, slow motion action, deep cutting — it also emphasizes the way the single combines spastic British drum ‘n bass beats with an American verbal flow, “performing a kind of cyborg fusion between the warmth of the human voice, and the coldness of machines,” according to cultural critic Steven Shaviro. Williams draws attention to this hybridity by placing Missy in both industrial and outdoor settings. She appears as both android, composed and programmed to dominate, and ultimately human, self-possessed and free of network control. Pop cultural delirium personified.

Missy Elliot ‘Supa Dupa Fly’ video, directed by Hype Williams

For the Busta Rhymes single “Put Your Hands Where My Eyes Can See,” Williams constructed a clip that consistently ranks on MTV’s greatest music videos of all time list. Rhymes told Williams that he believed the album that the single came off of, When Disaster Strikes, was different from the rapper’s previous records as both a solo artist and as a member of underground rap collective Lords of the Underground in that it pushed Rhymes’ tribal and African music influences to the foreground of his music. Seeing an opportunity, Williams used the Eddie Murphy vehicle Coming to America as the video’s primary reference. With the concept of an African lost in New York flipped, Busta is depicted as a New Yorker lost on a psychedelic journey into the soul of Africa as creative mecca. Busta wakes up in a lavish, Afrofuturistic-tinted castle a newly minted African king before getting chased by an Elephant, lavishing in the attentions of decadently beautiful women, and dancing a macabrely disorienting dance routine painted in dayglo tribal makeup. The video is seductive, thrilling, and even a little disturbing. Williams emphasizes Busta’s inherent otherness, a true hip-hop oddity, while ensuring an explosively entertaining piece of film.

Busta Rhymes ‘Put Ya Hands Where My Eyes Can See’ video, directed by Hype Williams

What we see in these videos, and throughout Williams’ filmography, is that Hype Williams basks in the projection of the one-dimensional image. To him, the surface is the reality. In his music videos, he wasn’t a portraitist attempting to puncture the facades of the artists’ images. No, for Williams the spectacle was the artist: Missy as a cyborgian Gen X feminist goddess, Busta as a surreal African prince, Biggie Smalls as New York’s kingpin pimp supreme. Williams respected the creative thought processes that these artists endured in developing their aesthetics, and used his own prowess and talent to give life to the performative images that they had cultivated for themselves. Hype Williams, and perhaps some of his music video contemporaries, reveled in what Baudrillard called the hyperreality of postmodernism; in his videos, you can’t distinguish between the superstar – the constructed image – and the human that lives underneath and has assumedly created the superstar as an expression of his own subjectivity. Williams makes the simulation into a reality, or, hyperreality.

And that is what, with some two decades of hindsight, makes Williams’ one feature film Belly such an exquisite postmodern relic and surprisingly innovative work of cinema. It is ostensibly a genre film, but I would dare anyone to actually relay the entirety of its plot. What is it actually about? Well, there’s something about two lifelong friends: an angsty psychopath named Tommy Bunds, played by DMX, and a reflective and morally aspirational player named — rather ludicrously — “Sincere,” who is trying to get out of the game, played by Nas.

Belly

True to Williams’ music videos, Nas and DMX aren’t portraying fictional characters so much as they are portraying the characters that they created for themselves and inhabited throughout their careers, but amplified. Bunds and Sincere are DMX and Nas post-exhalation of a methamphetamine hit: sharper, brighter, in focus. Bunds feels no remorse for who he is, he’s all “bark” and even more bite. He is aggression and self-assurance incarnate: pursue, pursue, pursue. Take what is yours. Sincere, ever reflective and contemplative, has lived the life of crime, but sees its ills, sees himself and his misdeeds as playing a part in a system that he perpetuates even though it was put in place by power centers beyond his control. Both descriptions aren’t far off from those that could be applied to the roles of Nas and DMX in pop culture writ large. With that, Williams successfully stretched the music video format that he pioneered over the duration of a feature film.

Shunning the conventions of plot, Belly, much like a music video, bathes in a hypnotic blending of tactile sound and decadent image. Like some dissociative narcotic, a Robotrip through the neon lit nether-realms of the New York crime world, Belly appears to drift in and out of consciousness. It often feels like the camera is coursing along through a dream, your gaze briefly appearing out of the ether to capture snapshots of a seductive and dangerous lifestyle. Consider its first scene. DMX and Nas waltz in slow motion into a club, cocking and loading their weapons, illuminated by the narcotized glow of blacklight. As the guns fire and the bodies drop, the scene embodies violence as sensuous freedom and exploits our desire to live outside the confines of our drab existences. What’s worse? Ten to twenty years of hard time? Or a lifetime of middle management? Hype Williams glamorizes the outlaw in particularly decadent, nineties fashion.

Harmony Korine Gummo

After that initial club sequence, the boys come home and Bunds turns on a movie. It happens to be none other than Harmony Korine’s Gummo: “It’s a sly inverse of the cultural-tourist racial dynamic that occurred with white boys like myself in the Nineties who were absorbing rap music videos—Williams’s primary medium,” lovingly pointed out Pinkerton.

No one has ever quite learned the connection between Korine and Williams, but it’s not hard to detect a kindred spirit of sorts shared between the two artists. Both are distinctively Gen X filmmakers. Both have made some truly extraordinary music videos. Both are devilish rebels, transgressors of norms who know how to trick capital into paying for their head-fucky exploitations. And finally, both are pioneers of a cinema that relies less on plot than it does imagistic oddities and singular atmospherics. And of course, Korine would return the favor when he released his own psychedelic exploration of the gangster outlaw lifestyle in 2012, Spring Breakers, and utilized much of the day-glo colors, slo-mo and wide-angle shots of Belly, proving that Williams’s brief foray into feature film had an outsized cultural impact.

Gummo was only out for a year when Belly went into production, emblematic of the hyper-referential nature of film and commercial art in the nineties and the ways in which cultural producers of the era cannibalized each other and everything else in sight, each putting their own perverse twist on everything else that was happening. As Ghostface Killah and Raekwon said, the nineties was the decade of “shark biters.”

Tommy Bunds and Sincere watch Gummo in Belly

It was Frederic Jameson who pointed out that postmodernism was defined by the inability to think historically. And I don’t know that Williams is incapable of thinking historically, but I do know that he created a visual universe in which history was irrelevant. In which the present was everything. Capitalism had already swallowed history whole, so Williams found a way to make and create art that wasn’t averse to commercialization, it was commercialization. It redefined advertising as something thrilling and provocative.

Jameson also said that the video “can lay claim to being postmodernism’s most distinctive new medium, a medium which, at its best, is a whole new form of itself.” However true that might be, it’s safe to say that by 1995, the music video form specifically had eclipsed the form of which it evolved off of to lay claim to that throne. Williams defined a form of art that was a commerce, an advertising of another form of art that also became a commerce. This cyclical nature of creativity and product defined art production in the nineties, and no one made it more gloriously libidinal than Hype Williams. Hip-hop’s look is inseparable from the videos that Williams created. He is hip-hop at its most outsized, most world dominating, least apologetic. And Belly, the cult artifact with outsized cultural importance, is his greatest experiment with the form that he birthed into existence. It is a time capsule. A zeitgeist. To watch Belly isn’t to watch a film, it’s to look at a time period that ended before it even started.