ANNOUCEMENT: I will not publish anymore content here. All of my self-published writing will be published through my new collaborative Substack project, SAFETY PROPAGANDA. Thank you!

The American Left And Its Double

The individual does actually carry on a double existence: one designed to serve his own purposes and another as a link in a chain, in which he serves against us, or at any rate without any volition of his own – Sigmund Freud

America’s urban enclaves erupted in joy and celebration on Saturday, November 7, as Joe Biden was announced president elect. According to liberals and leftists alike, we had ousted a tyrant from power in Donald Trump’s defeat (the irony of a “tyrant” being brought down by a democratic election is not lost on me). And yet, what was most striking about the celebrations that I witnessed while walking around the petty bourgeois hell that is Williamsburg, Brooklyn, was that there was something off about the whole thing. It was like there was an unwelcome phantom, like Poe’s The Masque of Red Death, lurking in the background of the debauched festivities. Against the atmosphere of kids wearing denim jackets with “I Voted” stickers covering the front pockets, drinking copious amounts of alcohol and chanting “JOEEEE BIDDEEENNN!” in the streets, there was a muted undercurrent of strange melancholy permeating the air; a barely detectable aura or menace. Mark Fisher noted that the most fascinating horror stories often to evoke “the weird,” or the presence of something in a space in which it doesn’t belong. The celebrations of the defeat of Donald Trump then was something like a non-fiction of the weird. There was a presence of something sinister and dreadful warping the character of the festivities into a disquieting pageant.

How could this be? We defeated a dictator, or so they tell me. But it is their disbelief in their own moral clarity and belief in Biden’s political program, or lack thereof, that animates the obscene over-reactions to the election results. Because we, as a people, did not defeat a dictator. No, instead, they, the ruling class, defeated a man who had simply become an inconvenience to them. Therefore, this past Saturday, all the fireworks and tears of joy and Black Lives Matter signages were an unheimlich of triumphalism. In our zest for defeating Donald Trump, an obsession fueled breathlessly by the media in all of its forms, we elected something so much worse. We elected the rule of the shadow. The invisible power that dominates us. Silicon Valley, Wall Street, the military industrial complex, and the security state. Those dark forces that the Democratic Party and the American left are struggling to conceal their allegiances to. Flummoxed with racial paranoia and high on tech firm-focus grouped activist slogans, the country collectively rejoiced over Biden and Kamala Harris – brutal carceral statists both responsible for some of the most damaging public policy passed over the last three decades – rising to power. So, was it really joy animating those street demonstrations, or were there unspoken dynamics underpinning all of this? When our choices were narrowed to an oafish game show host and corrosive corporate power, we chose the latter. But that’s hardly worth celebrating. So the festivities last weekend had, quite literally, a dual character. A double. A doppelgänger. And that doppelgänger manifested as something like a spectral mass resignation that lurked beneath the performative jubilee. Or perhaps this twin character was something else, something even worse: the naked thirst for power. The shadow self, or the double, is found within all our contemporary political relations, and in mining the double we better understand the true natures of the forces and narratives that produce and maintain our systems of control.

Andrew Wyeth Winter (1946)

I can imagine these “celebrations” being painted by Andrew Wyeth. Upon first glance, it all looks common and normal and even merry. The people joyously take to the street in exultation for progress and political hope. But when you look deeper, when you pierce beneath the image and excavate its content, we can start to identity the dark undercurrent beneath the one-dimensional image. Wyeth often painted many images over a gesso board or paper only to later erase them or paint over them with another image that he believed better expressed the work’s “inner spirit” of the erased or the “underpainted” image. This technique allowed Wyeth to disentomb the strange within the familiarly rural Americana settings of his paintings.

If we were to erase over the image of the celebrations that manifested in response to Biden’s victory, what would we find? What would the “inner spirit” of the rejoicing liberal masses look and feel like? Despair? Maybe a little. Cynicism? Certainly so, at least in the cases of party apparatchiks and their corporate paypigs whose careers and financial situations will improve with a corporatist Democrat in the Whitehouse. Abdication? Yes. That’s it. The same American leftists – from Antifa affiliates, to DSA members, to milquetoast suburban liberals – that spent the entire summer burning bodegas to the ground on behalf of Black Lives Matter are now out in the streets ringing cowbells and dancing like buffoons to applaud the election of the writer of the 1994 crime bill and a brutal prosecutor who put parents in prison for their children’s school truancy. Are these people even self-aware enough to experience the level of cognitive dissonance that would be warranted when living with these ideological contradictions? The Freudian double of the festivities around Joe Biden winning the presidency is the apotheosis of what Fisher called “capitalist realism.” What is hyperbolically being hailed as the defeat of a dictator is in actuality the reinstatement of a blood thirsty status quo and the totalizing rule of the security state. Under this new dominion, we can expect obscene censorship (look no further than Silicon Valley’s halting of the flow of images of Joe Biden’s son Hunter Biden smoking crack and getting blow jobs for evidence of more of what’s to come), further spiraling inequality, the silencing of Marxist sentiment, the probable invasion of Venezuela and genocidal war waged on Iran, and a media that will run cover and propagandize on behalf of the new regime at all costs. Does anyone actually believe that American dictatorial rule was more likely to come from Donald Trump (who barely had any institutional support in the first place) than our country’s most insidious sectors of centralized power? With a neocon blue dog democrat back in the Whitehouse, protected by a war machine propaganda apparatus the likes of which the world has never before seen, one thing is for certain: “A totalitarian future is assured,” observed writer DC Miller.

Bruno Schulz Pilgrims

If there is one positive outcome of this election cycle, it’s the demonstrable discrediting of the vast majority of what passes as the American left. So many of its institutional figures proved themselves to be little more than, as the What’s Left podcast host Aimee Terese has fiercely pointed out again and again on her show and her Twitter, branding consultants and useful propagandists for the Democratic Party and, by extension, the left side of capital.

After all, it was less than six months ago that Intercept journalist Ryan Grim, Current Affairs editor Nathan J. Robinson, journalist Katie Halper, and hordes of rose emoji Twitter accounts were using Tara Reade’s flimsy accusations of sexual assault to discredit the presumptive nominee Joe Biden as a rapist. Not only were these accusations already of no use to us (electorally anyways, given that the American left had already totally failed in doing what was necessary to make Bernie Sanders appealing to a broader voting public), these same actors then had to turn around and support a man that, according to them, was a rapist. The political economic function of these leftist figureheads has never been clearer: corralling people back into the Democratic Party when it matters the most (in the months leading up to the election). Beneath their raggedy vintage hipster clothes is a blue Armani suit with a flag pin on its lapel clawing its way to the surface. The activists of today are the party bureaucrats of the nearer than you could imagine future. Benjamin Dixon, one of the more gleeful distorters of realpolitik, followed up rows and rows of tweets expressing transcendent joy over Biden’s win with, “I do appreciate the Democrats making it so easy to demonstrate to the extremely liberal audience I built fighting Donald Trump why the Dem establishment sucks and needs to be replaced primary by primary.” Again, a peculiar uncanny emerges from sentiments like these. What sounds like resistance to the Democratic Party is functionally no more than allegiance to it. Dixon and his ilk aren’t fighting for justice, they are vying for better positions within the party machinery, pitching themselves as its next generation. “Orange man Drumph very bad” or “Joe Biden a war criminal but we gotta get the orange man outta office” are rhetorical devices of dual character. By feigning opposition to the democratic nominee’s politics while reinforcing the “lesser of two evils” binary, they are doing effective branding for the party targeted at those voters who might otherwise be inclined to sit the election out, AND by demonstrating their importance to the party (and its infrastructure) they are climbing higher up the ladder of social and political capital.

But the mask is off. We can see these leftists for who they are. When you can look beyond the radical posturing and the chants and the raised fists of leftist media figures you can see their true faces; as lascivious and ravenous for self-serving pleasure as the horny men ogling prostitutes in the drawings of Polish surrealist artist and writer Bruno Schulz, leftists are little more than market actors working within their own class interests to position themselves higher up in the elite. “The activist” is the doppelgänger of the bureaucrat. The idealist and the careerist: one and the same.

In the race between Donald Trump and Joe Biden, the true nature of the left has never been easier to understand. If you’re truly unaffiliated with the Democratic Party and solely interested in imbuing the working class with the kind of radical consciousness that could eventually bring forth a toppling of the ruling elite, wouldn’t you opt out of electoralist politics unless? Or, even if you genuinely believed that choosing the lesser of two evils in a presidential election was important, but you weren’t a democrat or involved in party machinery, wouldn’t you then try to go through Biden and Trump’s platforms issue by issue and make a substantive judgement based on a material reading of their politics? I hope you would, of course, but leftists are democrats in the United States. There could be a self-avowed socialist running on a GOP ticket and American leftists would still support the Democrat, citing the same culture war issues that they always cite. Biden’s policy record is among the most harmful in recent political history, he has surrounded himself with Bush-era neocons, and has refused to concede on any reform that might lift up working people. Trump, on the other hand, hasn’t started any wars. He did some substantial prison reform. Hell, he even vetoed a renewal of the Patriot Act, and got little to no praise for it. “What if Trump could be shown to be less destructive than the Democrats in nearly every single policy dimension?” asked writer Anis Shivani shortly before the election. From what we’ve seen, it wouldn’t matter. Leftists vote Democrat. If it’s not in their blood, it’s in their ambition.

Our politics suffers from psychosis. Specifically, it suffers from a split personality disorder. Every figure, narrative or story in American politics has a public character that tells us it’s one thing but is driven by a shadow self that reveals its true motivations. Joe Biden, “savior of the country,” is a brain dead reactionary and empty vessel for corporate power. Donald Trump, “fascist dictator,” is a fairly milquetoast liberal with vulgar rhetorical style. The Democratic Party, “party of the marginalized,” represents 51 out of the 55 wealthiest districts in the country. The fear and rage of liberals and leftists about their country descending into fascism and their concern for immigrants and “people of color” is little more than moral coverage for them ruthlessly acting within their class interests. And those cool kids in the hip urban hubs taking to the streets to celebrate the victory of Joe Biden and the “downfall of a tyrant?” Their shadow is alienation. Their double is defeatism. Their joy is undercut with a state of hyper cognitive dissonance: “Maybe this is the best we can do,” repeats as mantra in the backs of their deluded minds. Zizek made the insightful observation about Scorsese’s Taxi Driver that when Travis Bickle practices his vengeful murders in the mirror, a direct manifestation of Lacanian mirror stage, “he shows us that he perceives HIMSELF as part of the degenerate dirt of the city life he wants to eradicate, so that, as Brecht put it apropos of revolutionary violence in his The Measure Taken, he wants to be the last piece of dirt with whose removal the room will be clean.” This too applies to bourgeois liberals’ and leftists’ obsession with Donald Trump. They never truly believed that Trump was a fascist, but in Trump’s success they were forced to stare at their own decadence reflected back at them in a particularly grotesque form. Trump’s existence on the political stage was symbolic of the failures of their politics. In their Trump Derangement Syndrome and irrational desperation to remove Trump from office, they merely desired to put the mask back on the bloodthirsty status quo that is within their interests to protect, to different degrees. Those rich hipster trust fund kids weren’t drinking and snorting coke in celebration of progress. They were rejoicing over the return of a brutal liberal order without the impolite aesthetic that Trump so enthusiastically employed. Under the guise of celebrating justice, they were rejoicing for injustice that benefits them as the future elites of our country. The same people who tell us that they are concerned with the welfare of at risk communities, look straight into the eyes of Trump’s mostly working class supporters – the same people who saw their jobs shipped overseas due to policies written by the politicians that leftists propagandize for, only to then be prescribed opiates for the pains and aches they endure due to the miserable jobs they waste away at every day, enslaved to the same pharmaceutical companies who pay their leftoid political antagonists – and laugh. They drink, dance, and luxuriate in the misery of ordinary people. The doppelgänger of social justice is, now more than ever, thirst for power and domination.

Thomas Moore Alone

In Thomas Moore's Novel 'Alone,' Happiness Is A Temporary Kink

In Thomas Moore’s fiction, interpersonal relations and human experiences are dulled by the digital networks and platforms that are inherently intertwined with them in liquid modernity. The influx of cyber communications into our personal lives has saturated them with the vaguest sense of unreality, but not an “unreality” in the sense of “dream-like” or “surreal.” Instead, what Moore’s characters seem to experience is a subconscious unease that I often feel in my own life: “Is this real? Is my life a narrative arch or a simulation of one? Do I even exist at all?” In Moore’s fiction, living is more like lingering, a state of sentience beyond a spiritual death.

Such is the by-product of cyber communications. Instagram and Twitter have largely replaced authentic communities; intellectual, artistic and otherwise. Moore provocatively illustrates these holes within our lives that dull our experiences and emotions. Joy, love, desire, pain, sadness, connection, disdain: when these emotions play out in cyberspace, we simulate feeling these emotions at all. This leaves us pondering whether our lives have any material weight. Moore’s characters experience this confusion as a dulled, gnawing despair and a resigned, pathetic acceptance. Maybe they don’t exist? Maybe that’s ok?

In Moore’s novel Alone, recently published by Philip Best’s (also noise musician of Consumer Electronics and Whitehouse fame) Amphetamine Sulphate imprint, an unnamed narrator endures a prolonged breakup with his semi-involved boyfriend of eight months Daniel. Early on in the novel, the narrator proclaims: “I’ve always been disgusted by my own love.” Moore’s previous novel Into My Arms was broadly concerned with its protagonist’s desire for connection. <i>Alone</i> then is the logical extension of that theme. Its protagonist has resigned himself to loneliness and solitude and is attempting to find peace within disconnected solace.

Darja Bajagic Ex Axes Pink Sweater

In a post on Dennis Cooper’s blog, Moore chronicles the art and texts that were on his mind throughout the Alone writing process. Concepts related to death and spectral lingering post-mortem are the connective tissues throughout these disparate works. A series of screen-printed axes by Darja Bajagic that depict missing and murdered women on the blades, their images continuing to proliferate digitally reminding their loved ones of their absences and their communities of the violence that lurks around the corner. The final three episodes of The Sopranos are iconically morbid – from the attempted suicide of Anthony Jr. to the deaths of three major characters – but the series provocatively robbed its audience of the sense of finality that deaths typically yield, opting to fade to black and allow us to ponder (literally forever) the fate of Tony Soprano (the single greatest character of the 21st Century). The death of Tony isn’t material, he lingers on spectrally. Tony Soprano and all his mediocrity is a stand in for us, and as long as we exist, so shall he.

Finally, Moore cites Marguerite Duras’ The Malady of Death, a novel in which a man hires a woman to live with him by the seaside so that he can “learn to love.” The attempt fails, with the woman telling him that he has “the malady of death.” This is the mode I choose to contextualize Alone within. This isn’t solely a text about loneliness, it’s a text about the acceptance of loneliness as an acceptance of death itself. In his decision to slowly let his relationship erode due to his innate “disgust with his own love,” Moore’s protagonist accepts his own symbolic death. He immerses himself in the digital world – in Grindr and other vaguely hollow methods of digital communications – and lets go. Is this not cyberspace’s ultimate function? By choosing to live within it, we tacitly accept to vanish from our actual lives. We choose death over life. We float through the web immaterially, averse to our own corporeality.

Duras’s influence is all over Moore’s writing, even if he distills that influence into a hyper-contemporary sphere of digital language and late modern pop cultural reference points. Like Duras’, Moore’s novels are textually short but emotionally rich, meant to be consumed within a single reading session. Duras’ text emphasizes an irreconcilable awkwardness between man and woman. Alone, however suggests that that awkwardness is not limited to heterosexual relationships. This tension simmers between all interpersonal dynamics.

Moore’s character is not devoid of desire or love, he is just uncomfortable with it, and opts out. He opts for loneliness. “Loneliness has been the one constant,” he writes. Loneliness in this novel is a signifier of stability. Moore rejects happiness, seeing it as a temporary kink or perversion that cannot and should not be held onto. “The idea of happiness as a goal rather than a transitional state is dangerous and much more damaging for a person to carry around than just knowing that everyone is fucked in some way,” writes Moore.

In her text on melancholia and depression Black Sun, French literary critic and semiotician Julia Kristeva devotes a chapter to Duras’s The Malady of Death. In Duras’s text, Kristeva finds an “aesthetics of awkwardness” that emphasizes the fundamental gap between the sexes that occasionally reveals “the abyss” of human despair. Moore’s is also an “aesthetics of awkwardness.” Throughout the novel, the protagonist finds himself either incapable of or too apathetic to coherently communicate with his partner and friends. His stymied communications are the origins of his resignation into loneliness. Seeming to comment explicitly on his “aesthetics of awkwardness,” Moore writes: “Language is a lie that we are guilty of and have told so many times that most of the time we either believe it or we are too tired to be able to fight off.”

Jonathan Brandis in It

Moore’s incorporation of the language of the Internet into his literature invites humor into the work while also clarifying his critique of contemporary digital life as a kind of death (of love, of connectivity, of “will to power”). The narrator poses the provocative rhetorical question: “Has Grindr killed psychic gay powers?” He notes the rise of Grindr hookups as the death of cruising and, thus, the death of intuitively primordial connection between men.

Throughout the duration of the novel, the prolonged breakup between the narrator and Daniel is prolonged by the introduction of a teenage prostitute named Joseph. Joseph was a childhood Youtube star (that Moore chronicles the depths of his adolescent child star crushes throughout the novel — from Edward Furlong to the 1990 mini-series adaptation of Stephen King’s It’s Jonathan Brandis — seems pertinent here) and started talking with pedophiles on the Internet as a means of alleviating boredom. Joseph, too young to remember anything resembling authentic intimacy, asks the narrator how men hooked up before Grindr. The concept of a non-simulated and not digitally facilitated desire is alien to him.

A few chapters are solely dedicated to Joseph’s johns and the messages they leave on his dating page evaluating his sexual performance and perhaps even more pertinently how “real” he seemed to act in his performed desire towards them. One such john is increasingly pathetic as he gasps for Joseph’s love and affection. This is all that’s left, Moore suggests, the alienation of the contemporary condition is artificially mitigated by the technology we use to conceal our despair and our loneliness.

Alone’s narrator often ideates suicide. His strongest urge towards suicide, he says, erupted from a spontaneous bout of group sex with two friends. This feeling, he says, was indescribably beautiful. What Moore suggests here is that these acts of spontaneous decisiveness are a portal to the ethereal. In group sex and in suicide, both non-passive, engaged and non-verbal decisions, you grasp the real unmitigated by the trappings of contemporary life. Moore pines for a human existence untarnished by media, technology and communications, for humans to be spirits brought together by desire and death, “Back in the woods, everything makes sense when it’s blurred,” he writes. “I wish that we were all ghosts that could merge onto another, blur and then separate beautifully and alone.”

Genre is Obsolete 3 (The Return)

So, Genre is Obsolete is back, sort of, untethered from the editorial demands of a publication vying for attention is the marketplace of ideas. I am, of course, also vying for attention in the marketplace of ideas, but while I’m self-publishing this you can expect it to encapsulate all that I’m trying to say with these “reviews.” This is, one-dimensionally, a column about recent releases of experimental music that defy typical genre classification or subvert genre form, but more broadly, I am attempting to explore “genrelessness” as a metaphor for the lack of structural cohesion that defines the social decay we are experiencing in late modernism. This is cultural criticism. I’m not interested in simply telling you whether a piece of music is good or not. But rather, I prefer to use these obscure works of art as a direct portal into the mystifications of the contemporary social, cultural, and political realm.

In this column’s namesake essay, philosopher Ray Brassier writes: “‘Noise’ has become the expedient moniker for a motley array of sonic practices – academic, artistic, counter-cultural – with little in common besides their perceived recalcitrance with respect to the conventions governing classical and popular musics.” He continues, “It refers to anomalous zones of interference between genres.”

This analysis of the epistemology of the term “noise” doesn’t just give us a critical tool to isolate and understand the component parts that define noise and experimental music, but can also be applied as a metaphysical matrix to interpret, comprehend, and critique the dizzying contradictions of life in late capitalist America, and the broader West. “Anomalous zones of interference” is such a potent, forceful use of language that could be extracted from a much broader and complex interpretation of culture. We are living in a time when much of what passes as “radical art” is little more than propaganda for the left liberal elite, as the mode of production has internalized cultural leftism into its hegemony while society remains immiserated and alienated beneath the crushing despair of market capitalism. The “hipster right” has become the home of the nihilist aesthete. Free from the ideological constraints of the left liberal bourgeois, populist right wingers can indulge in the transgression of culture. It shouldn’t be surprising that some of the best art criticism happening anywhere is on hipster right wing podcasts like The Perfume Nationalist, because these thinkers and artists are outside of the hegemony.

And though my politics still fall into a left Marxist categorization, I now feel liberated from any radlib sentimentalism that may have been holding me back. I want to write about art and music and books that challenge the orthodoxies of bourgeois morality and leftist hegemony. I want art that flat rejects the world we live in, and seeks to incept within it a sense of dissent and rage. This column shall analyze “anomalous zones of interference” in avant-garde music and in the society at large. If you truly hold contempt for the social and political order (and no, that doesn’t mean you are “anti-Trump” or support BLM, as both those stances are totally compatible with the fealty demanded of you by your oppressors), if you want to make art that deconstructs it and exposes its lies, then I am your brother-in-arms. This column is a microcosm of a broader camaraderie being formed. We are politically and ideologically diverse, with numerous theories and analyses of what is wrong in our world, bonded by our opposition to the false spectacle around us. Schopenhauer believed that noise was the death of intellectualism, “pure distraction.” But no, now the whole culture has become the distraction, a fiction outlined by the ruling elite and scripted by its interlocutors in the media and the NGO industrial complex. They are our enemies, and noise is a weapon through which we challenge them to show us their true faces.

John Wiese Escaped Language (Gilgongo)

Sissy Spacek Featureless Thermal Equilibrium (Helicopter)

Sissy Spacek Prismatic Parameter (Gilgongo)

Through LA-based noise auteur John Wiese’s vast discography, we further our comprehension of noise as essentially a genreless entity. Noise is a philosophical ideal, not a specific style or genre. Noise is a transcendence of form, or a formlessness, to use Rosalind Krauss’ preferred terminology . It is, quite possibly, even a religion. Wiese has long used different instrumentations, stylistic approaches, and structural formats to conjure noise forth into existence, worshipping at its altar. In a plethora of recent releases, Wiese demonstrates how noise can spew forth from any and all manner of sonic arrangements.

The music that Wiese makes under his own name is slippery. Like the codeine promethazine that drips down the cracks of your mouth during those opiated splurges, it oozes. An Angeleno weirdo and peculiar intellectual of sorts, Wiese’s approach mirrors that of Los Angeles-based artists like Paul McCarthy (who he’s published books by) and Mike Kelley; Wiese is essentially a collagist, assorting the sounds of the world into their most psychotically hallucinatory permutations. He locates the chaotic truth of this world in these microtonal skrees.

Escaped Language, a 2017 release recently re-published by Helicopter, is a live composition recorded at Présences Electronique Festival that condenses dimensions of pseudo-contradictory narrative implications. Its one 17-minute track opens awash in gorgeous, meditative ambience that erodes the walls of the ego, leaving space through which the chaos ahead can seep through. Lynchian lounge horn arrangements interweave with shards of noise and blue balled, throbbing bass. The arrangement’s closing two minutes are Wiese at his best, in which hissing noise blends into the overwhelming density of the atmosphere evoking the specters of Shirley Jackson’s Haunting of Hill House, enraged and violently obsessed with their own traumas.

With his long-running Sissy Spacek project, Wiese has explored the noise that can be extracted from something more resembling a trad rock format. Sissy Spacek is, functionally, a grindcore band. Its songs, historically, are blink and you miss them explosions of compressed metal and hardcore-influenced rock. While clearly deconstructionist in mindset – from Sissy Spacek’s first self-titled EP in 1999, Wiese seemed to be channeling the digital grindcore of Agoraphobic Nosebleed into manically collaged, stop-start freaked out blasts of noise – Sissy Spacek also sets forth conceptual conditions from which we can interpret the noise that is achieved, even if accidentally, in the more extremist sub-genres of guitar driven music. Certainly, on the topic of grindcore, the genre’s forebears often teetered on the edge of a rock format while the dizzying velocity and ferocious volume of the music constantly threatened it to tip over the edge, into the abyss of noise; or rather, the pit of genrelessness. Certainly, the first two Napalm Death records, Brutal Truth, and Agothocles all walked that tightrope between conventional rock form on one side and unnamable, libidinal chaos on the other.

Wiese has gifted us two Sissy Spacek releases over these last few pandemic-distorted, pandemoniac months. Prismatic Parameter, released back in March at the dawn of the “new world,” is indicative of the alien dimensions that Wiese has subsequently transported the Sissy Spacek project through, further and further away from anything normally associated with “grindcore” or even “noisecore,” since 2008’s masterful The French Record saw Wiese employing sound collage, electro-acoustic, harsh industrial beats, and the washes of coffin-like ambience that saturate the silence in-between black metal tracks.

Prismatic Parameter is a mammoth of a record, at an hour and 45 minutes it slowly pulls apart the synapses connecting the neurons in your brain, eventually resulting in a face melting anti-cathexis. The music finds a nexus between fucked electronics and the head-warped “fire music” free jazz of the likes of Brotzmann or Borbetomagus. Horn sections and an onslaught of jazz live drums weave through the mess of distorted electronics and sound shards, yielding a record difficult to digest but well worth the constipation. The dizzying percussion comes courtesy of the virtuosic improvisational percussionist Ted Byrnes, who through acts of heroic athleticism manages to keep this turmoil contained, to a degree. Also, Sissy Spacek’s oft-drummer Charlie Mumma, also the drummer of avant-garde black metal band L’Acéphale, is on here as well, allowing Wiese to explore this cosmic connection between the more extreme end of jazz and improvisational music and the more experimental ends of metal and extreme music (similarly to musicians like Weasel Walter and Mick Barr). This album is a helluva commitment, but in less music-drenched and horrendously depressing times I wager that it would become an object of cult fascination in the underground.

And while I know this section of the column is getting long (I don’t have an editor so fuck it, skip around if you want), I also have to mention Featureless Thermal Parameter, released early in August, that exists at the other end of Sissy Spacek’s sonic continuum: ferocious and berserk blasts of avant-sleaze noisecore. The album’s tracks are mostly under the two-minute mark, and employ no-fi black metal screams and guttural grindcore barks to hold conversation with the extreme metal that Sissy Spacek has long sought to destroy, stitch back together, and present as something new. On records like these, Sissy Spacek becomes the band for those who hear Extreme Noise Terror, or power violence bands like Spazz or Charles Bronson, and wish for something even less resembling traditional format. Pure annihilation of rockist sound, Sissy Spacek is as vital as ever.

Mosquitoes Minus Objects (Ever/Never)

Komare The Sense of Hearing (Penultimate Press)

In an essay she wrote on the pioneering “Cinema of Transgression” filmmaker Beth B, poet and former Teenage Jesus and the Jerks front-woman Lydia Lynch writes: “We used music and art as a battering ram and a form of psychic self-defense against our own naturally violent tendencies; an extreme reaction against everything the 1960s had promised, but failed to deliver.”

No wave, while often recognizable as an austere, atonal, and fiercely distorted kind of noise punk made with rock instrumentation, is more an ideological position than it is a recognizable genre. From its early origins in the downtown Manhattan of the 1970s, it already counted vastly different sounding bands amongst its ranks. The viciously deconstructed punk of Mars had little to do with the spastic lounge jazz of The Contortions, and the modern composition infused punk jams of Theoretical Girls sounded little like the nihilistic guitar sleaze of Teenage Jesus. But what united these bands, and all artists that would employ no wave sensibilities later (from the Chicago neo-no wave of The Scissor Girls and The Flying Luttenbachers to current bands like Guttersnipe), is a deep skepticism of there being any inherent radical potential within music or subculture. Only through the annihilation of tradition, or “genre,” can the transcendent and radical be attained.

This is the connection that UK-based trio Mosquitoes have to no wave. In no way are they hauntologically recreating music of the past, but rather the band employs the no wave philosophy to unearth new terrain in the quest towards anti-rock enlightenment. The trio’s recent 12” EP, Minus Objects, is utterly fragmented, with each musician seeming to create separate parts that barely weave into one another, while a persistent gnawing darkness engulfs the composite whole of the sound, like the extraterrestrial color of Lovecraft’s The Colour out of Space.

Two of the group’s members met at Fushitsusha show in the late ‘90s, and like Keiji Haino’s group, there is an aspect of the dark side of psychedelia here. The sound is so alien to what is normally associated with rock, it seems to exist within an abyss that threatens to pull you into it, deeper and deeper, until your ego dissipates into the ether. A fitting soundtrack to the horrifically untethered sensation that follows a DMT hit, connecting you with a world without us that humans are barely capable of interpreting. This is a music with a kind of cosmic pessimism. The opener, ‘Minus Object One,’ interweaves squiggles of synth noise, slow, throbbing base, and nonsensical shouts, an introduction to a dimension beyond. But the album works best when Mosquitoes immerse themselves in dank atmospherics, enveloping the listeners in an otherworldly dread that I’ve seldom ever heard achieved by rock music. Mosquitoes are, in a way, a no wave answer to The Caretaker or the painterly dark ambience of Aseptic Void.

Komare is something a companion band to Mosquitoes (“Komare” is the Czech word for mosquitoes), but in reality is the same project minus one part. Born on a day when guitarist Clive Phillips couldn’t make it to Mosquitoes rehearsal, Komare finds the other ⅔ of the band Dominic Goodman and Peter Blundell focusing solely on electronics to further fragment and minimize the group’s sound. The results are every bit as fascinating. Komare isn’t “better,” but instead demonstrates the multifaceted ways in which these musicians can approach the aesthetic that they’ve now been refining for years. This release finds the group processing human vocals through mechanic effects, begging us to hallucinate a future in which such binaries no longer hold any meaning. One could make the typical William Gibson reference here, but Komare works in pure abstraction, giving us only the sense of the future, rather than a narrative of it. Anxiety, of course, is the prevailing feeling of late modernism. Certainty has been liquidated into the amorphous flows of the market, reprocessed as looming, muted dread. This anxiety saturates Komare’s sound, which is hard to pin down. With so much empty social justice rhetoric being espoused in avant-garde music, one longs for the no wave sensibility that renders such ideas meaningless. Mosquitoes/Komare seize the awful zeitgeist by shattering the walls of form, finding a new art in the intermixed and indistinguishable rubble that remains.

Ceresco Union Ceresco Union (Maternal Voice)

Ceresco Union Spinning Gears (Tesla Tapes)

I was very happy to hear from Joseph Charms who put me onto his new project Ceresco Union, but also rather sad that he was done with his band Errant Monks. Errant Monks’ albums The Limit Experience and Psychopposition were absolute favorites of mine in 2019. Those albums chronicled Joseph’s battle with alcoholism and delirium tremens and dripped with an atmospheric psychosis. Walls of noise brushed up against punk-techno throbbing aggression and Joseph’s embittered but resolved spoken word musings. They crackled with the cacophonic emotional range of a man wracked with paranoia as his central nervous system pieces itself together again. But they also were imbued with the strength and sense of purpose of someone dedicating all his energy towards his quest for self-emancipation.

With alcoholism behind him, Errant Monks is dead, and Cereso Union lives. With two new releases, Ceresco Union on Maternal Voice and Spinning Gears on Tesla Tapes, Charms constructs an abstract sequential narrative to those earlier Errant Monks releases. Though the alcohol dependency is mostly successfully vacated from his neural reward pathways, he is in the awkward and alienated headspace of early recovery. This is strange music, not as extreme or loud as Errant Monks, but marked by a sense of unease and self-consciousness.

I’m reminded of the months I spent in social isolation following my final opioid withdrawal. I lost more friends in those months than I did in my darkest days in my dalliances with junk. Why? Well, it’s hard to explain. CNS depressant drugs, like smack or booze, dulls the edge off the common anxiety and unsureness we experience as human beings, and when you lose that buffer, you start to act….. Strange. I’d cry at inappropriate times, you see, I’d over-share my struggles with drugs to people who barely knew me. If you met me at any point between August of 2012 and February 2013, the first things you would have learned about me were my name, and that I was a recovering junkie. You become alien to yourself, walking the autism spectrum back to some sense of emotional normality. It’s a horrendous experience, really, which makes it all the harder to not backslide back towards the warm embrace of the chemicals. That’s what Ceresco Union evokes for me.

Disgusting Cathedral Adventurer’s Despised and Rejected

Alex Lee Moyer’s documentary TFW NO GF shocked leftoids and liberals alike earlier this year by positing the theory that the alt-right and incel phenomena that have played out across the internet sphere over the last few years might just be connected to a set of specific economic and material conditions. When American leftist magazine Jacobin tweeted this groundbreaking take on the film (which they postponed for five months after the film’s release, emphasizing the publication’s typically abject cowardice in the face of their woke and decidedly unsocialist readership), their followers were just aghast! “WOMEN ARE POOR TOO AND DON’T SPEND ALL DAY POSTING VIOLENCE ON SOCIAL MEDIA!” exclaimed one particularly exasperated reader, in a post not unusual given the overall response to the tweet. But this is where Moyer’s documentary was so successful. How could any Marxist not view this subculture through the prism of economic failure? How could the material conditions of a jobless, hopeless, uneducated and poor group of young men not warrant a materialist critique? Moyer forced the DSAers to reveal themselves. They aren’t socialists, they are liberals, viewing the world through the binary of good and evil.

One of the film’s most recognizable characters, internet poster Kantbot, became the closest thing to a breakout star that could realistically be produced by a film about dejected, angry, male youths. Kantbot fancies himself something of a crackpot philosopher, a self-help guide for the perpetually unemployed and unlaid. Throughout the film, he recalls directing his followers away from hate posting about women on 4Chan and towards the philosophy of his influences like Friedrich Schelling and Immanuel Kant. Kantbot can best be interpreted as a sublimation of the incel’s alienated condition, directing the incel towards idealist philosophy and transcendence. “It’s all going to be ok, it’ll all be ok,” he repeats to the camera towards the end of the film, replacing bottomless hopelessness with just the vaguest sense of light at the end of the darkness.

However much I might be reaching with this long-winded metaphor, self-described “dungeon-synth” project Disgusting Cathedral appears to do for rank, hideous, sickly electronic sounds what Kantbot does for incel ideology. The isolated parts of debut album Adventurer’s Despised and Rejected; casio keyboards, Eurotrack synths, Nintendo DS music apps, obsolete FX, and tape manipulations; shouldn’t amount to much more than the dank, squiggly, head fucked electronic noise that I usually write about in this column. And yet, those components congeal into something…. More. This music is deeply unsettling, no doubt, but it’s also exalted, cosmic, and beyond. It’s so depressing what passes as “psychedelic music” in 2020 (I mean what isn’t depressing in 2020, really?). It’s all just post-Loop, wah wah guitar-driven rock music, or Sunburned Hand of the Man-esque freak folk 15 years too late. Psychedelia shouldn’t be a genre, but an extra-dimensionality. Todd from Ashtray Navigations told me that he sees psychedelic music as “music in 3D,” and that’s what I’m looking for. Music with dimensions, and drama. Music that sucks you into a void before caressing you in its womb and spitting you back out into a new world, or the same world, but an altered version of it. That’s the kind of psychedelia that Disgusting Cathedral is putting forth. There are perhaps some formal precedents here in young James Ferraro’s noisy duo The Skaters (with Spencer Clark), or perhaps Helm’s early project Birds of Prey (with Steven Warwick), but there are perhaps even more chemtrails and psychic distortions here. I really dig this.

Metadevice Ubiquitarchia (Malignant Records)

A lockdown record courtesy of Metadevice, also known as Portugal-based noisenik André Coelho, stripping any recognizably human features from the Metadevice sound in favor of the warped, decayed electronics that are indicative of a genreless culture in a dying world. While Metadevice’s previous album Studies for a Vortex made use of spoken word vocals in its documentation of a culture slowly wilting away piece by piece, Coelho leaves this album empty of language. Language, this music suggests, fails to capture the all-encompassing suffocation of the contemporary political moment. Wittgenstein wrote that “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” But what happens when the only world left is the ephemeral one that I’m currently mainlining my thoughts into, as I type away? This, the digital, is the only real. Locked in our homes, isolated from our common man, we inject our subjectivities into the information highway. Metadevice illustrates our bodies sublimating into our screens, like Videodrome without any choice given. We mutate, or we vanish into null. Outrage, confusion, misery. Nothing is material. It’s all happening in there, in here, a cold, dead atmosphere where nothing happens and everything happens all at once.

JK Flesh Depersonalization (Hospital Productions)

When I was an adolescent metalhead, Godflesh were one of the first “good” bands that I really got into. I was a subscriber to Terrorizer Magazine because it begrudgingly covered nu-metal bands like KoRn and Slipknot in efforts to hold onto a broader readership. I bought Godflesh’s final album of its initial run, Hymns, because Jonathan Davis was an outspoken fan of the band, and the name “Godflesh” fascinated my perverse 12-year-old brain. That album was a revelation, it was heavy but sublime, it sizzled with imagination and pulsated with sensuous rhythm.

Throughout my early life, I relied on famous musicians who I realistically could know about to introduce me to the underground through their interviews. Kurt Cobain gave me The Butthole Surfers and Flipper. Thom Yorke directed me towards electronic music, like Aphex Twin and Autechre. Thurston Moore made the case for Japanese noise. But perhaps more than all of them, Justin Broadrick was my most important tastemaker. Everything from punk rock like Crass and Discharge, industrial music and early power electronics like Throbbing Gristle and Whitehouse, dub, techno, Broadrick demanded I broaden my tastes. Even just being a Broadrick fan could open the floodgates to the sounds beyond, given his vast discography and diverse stylistic range: the grindcore pioneering of early Napalm Death, the industrial hip-hop of Techno Animal, the lush, guitar droning shoegaze of Jesu, and the ferocious torrents of noise in Final. Being a Broadrick fan is a commitment to dexterity and open-mindedness.

With that fawning text out of the way, let me declare that it is Broadrick’s aggressive techno project JK Flesh that holds the mantle of being my favorite music that Broadrick has ever created. Why, you ask? Well, what is so special about these vicious dance beats is that they seem to embody every aesthetic realm that Broadrick has ever explored. The aggression of Godflesh, the grooves of Techno Animal, the expansiveness of Final; they’re all here, compressed into these rhythms. Broadrick’s techno is minimal, but inhabits so much. I’ve struggled to make a “genreless” case for techno, given that it is so recognizable as an easy-to-pinpoint genre. But nevertheless, what techno can do at its best is to vacuum disparate genres into its formula, absorbing new bodies into its organism, each component part adding to the multi-headed beast while maintaining its structure as a single entity.

JK Flesh’s newest release Depersonalization is brief, taut, and rife with sonic potentialities. Though not on the masterful level of Rise Above, it makes a potent case for JK Flesh as the apotheosis of Broadrick’s vast sonic terrain. It, as a project, is at the top of a pyramid that the artist slowly climbed towards his entire career. It’s like he learned to sculpt away at his sonic signifiers, revealing their true essence, and took those essences and carved them into something mesmerizingly sharp and clear. It’s dance music imbued with the essence of all the energy of extreme music and all the limitlessness of the avant-garde. It’s the genre of techno that suggests the philosophical territory of genrelessness.

Darius James

A Final Conversation with a Great Troll: Darius James and the Literary Deconstruction of Racecraft

Darius, I have a confession. When I first read your novel, Negrophobia, I wasn’t sure if I should like it. Your book presents its black characters as ghoulish and hallucinatory embodiments of some of the most flagrantly racist stereotypes laundered through 20th Century American culture. There’s the tyrannical and almost illiterate maid who abuses the novel’s bubbly albeit racial paranoiac, Paris Hilton-esque protagonist Bubbles. An evil witch doctor pulls rabbits out of Bubbles’ vagina in a horrific “Voodoo” ritual gone wrong. Hell, Darius, you even personified lawn jockeys as animate beings! What was I to do with this novel?

I was mesmerized by the way you structured it. It reads like an uncommonly readable screenplay: three acts, dialog blocks, expository setting descriptions. The banality and formality of the screenplay structure functions as a set of boundaries through which the chaos of your prose is contained within. Inside this semantic matrix, a vortex of violence threatens to explode outward – beyond its parameters and off the pages – by conjuring a chimeric atmosphere of grotesqueries, body fluids, and racial animosities. But, in being seduced by your prose, was I condoning racist propaganda? Were you tricking me into outing myself as something I never thought I could be? Your art holds a mirror up to its readers through which they see their reflections distorted and distended, face to face with the inner-ugliness we all struggle to suppress.

And while Negrophobia does force readers to take stock of their own bigotries, it doesn’t denounce them as evil for holding such animosities. Instead, it deconstructs the ways in which these bigotries are socially, culturally, and politically conditioned. What Negrophobia really is, is one of the most hilarious, provocative, and upsetting works of literary art to ever question the notion of race as a signifier and point of human distinction. If anything, it condemns the cultural fetishism of race that continues to define our discourse! Your book boldly draws attention to the fact that “race” only exists to the extent that racism exists! We have CULTURAL differences, Negrophobia declares in its exaggerations of ugly stereotypes, but racial difference doesn’t make us “different.”

The provocations of Negrophobia begin with its structure: a screenplay. By shunning the form of the novel, you dismissed the novel as the historical embodiment of literary genius. “Fuck that bourgeois shit!” you said. By using the screenplay format, you signal towards the legacy of blaxploitation cinema, an art form known for its use of stereotypes. But it was this choice that laid the groundwork for what Negrophobia became. In your text, the racial stereotypes become so absurdly grotesque and terrifying that they begin to liquidate the meaning that the stereotypes held in the first place. Instead, the stereotypes serve the function of making the reader aware of how stupid such stereotypes are at root. Everyone, regardless of their race, is inherently idiosyncratic. A singular entity. It doesn’t even matter if one conforms to a certain stereotype, the human subjectivity is always more complicated than that. Deeper and richer. As much as the psyche conforms, it transgresses. We’re all so very different, and yet, we need the same things: security, a home, love. By busting the stereotypes through the vicious exaggeration and fragmentation of the stereotypes, the larger purpose of Negrophobia unfolds.

One of the most troubling notions of identity politics, on both the political left and the right, is that both sides of it tacitly accept the notion that there are inalienable distinctions amongst us based on the levels of melanin in our skin. Through this minute physical difference, we are led to believe that the gaps between us can not be bridged. And it’s not just outright racists who enforce this fallacious belief, but also liberals who, either well-meaningly or cynically, think racism can only be overcome by deep engagement with race as a difference. This is an absurdity, and it’s the absurdity that animates your vicious critique of racism and racial difference in our culture, Darius! It’s the absurdity that drives the manic dreamscape of pervasive racial paranoia that is Negrophobia.

Political scientist Barbara Fields uses the term “racecraft” to describe the phenomenon in which racism produces the illusion of race as a material force. True to its name, this is an act of cultural sorcery that manifests on every side of neoliberal discourse. Right wing republicans will talk about and dog whistle towards “baggy pants” and loud rap music and black on black crime. Left liberals, conversely, treat the “black community” as a hegemonic voting block that unanimously shares political interests, despite the myriad class distinctions and varying degrees of power and influence within communities of people of color. The left liberal needs to portray its subject as a victim, because victimization in late modernism is the last virtue. Negrophobia, Darius, embodies the banal occultist practices of racecraft, in which people of different races are pitted against one another, and people of the same race with nothing else in common besides the vague similarities in their skin see them treated as one solitary unit. Black people. White people. Always at odds, never to find solidarity, much less any form of brotherhood or camaraderie.

In Negrophobia, the protagonist Bubbles is incapable of seeing race until it is amplified through the racialized stereotypes that you gleefully put to page. The stereotypes function as a provocation that demands that the reader think harder about what it means to live in a racialized society, while they also serve to illustrate the inherent hypocrisies within those readers, regardless of their race. As Fields says, race isn’t biological, it is merely a social construct learned and indoctrinated through racism. It is racism that creates the very phenomenon from which race materializes as an ontological force. Race becomes a social projection that is then largely performed. Bubbles can’t decipher “blackness” through physically seeing skin color, blackness only takes form within her mind through the racialized images and stereotypes that the characters she comes into contact with conform to.

The Cream of Wheat Chef. Louis Farrakhan. The Sun Ra Arkestra. Negrophobia illustrates the racial construct as a population persistently force fed Devil’s Breath while “the man” whispers stereotypes and racially loaded concepts into our ears as we drift in and out of consciousness. By the time that we awake, we are absolutely convinced that race is not just real, but so pervasive that it cannot be overcome. This is the terrifying conclusion of Negrophobia, Darius. Bubbles finally comes to terms with her “negrophobia,” her irrational racial paranoia and fear of black people, but at the same time, she finds that she can’t shed herself of her biases. They are too indoctrinated into her, like a cult religion. You can’t overcome what isn’t actually real. You can’t vanquish political voodoo. It’s hauntological, it’s everywhere even if it’s not there. Your pessimism, Darius, was brutal. But it was also prophetic. How can we overcome racism when the very notion of race as difference is enforced by racism?

These categories; “Race,” “blackness,” and “whiteness”; are implemented by the social and political elites to absorb the under classes into a vortex of incoherence, petty resentment, and hate. By fear mongering race, the global elite manipulates the working class into aiming their hatred at each other, leaving it unaccountable and free to wield power and amass wealth. Perhaps you were aware of socialist political scientist Adolph Reed, Jr. 's work while writing Negrophobia? Reed implores us to understand that “race reductionist politics are the left side of neoliberalism and nothing more,” he says. “It is openly antagonistic to the idea of the solidaristic left.” Congressman James Clyburne single-handedly destroyed Bernie Sanders’ 2020 campaign by appealing to his mostly black voters’ sympathies for Joe Biden’s allegiance to our first black president, despite the fact that Biden’s political record is responsible for mass incarceration, which has decimated black communities across America. This is just one example of the myriad ways in which the racial construct is abused by our power elites to mystify the stakes of politics and society. In the end, the bourgeoise is the solo benefactor of the contradictions.

These travesties occur because we are convinced that race exists, and we are convinced that race exists because racism made us believe it was from the moment we slithered out of the womb. Some critics took issue with the hyper-exploitative nature of your metaphors, such as when Bubbles is covered in soot and passing as a black woman only to say “If you insist on poking your fingers where they’re clearly not wanted, you could at least rub a little faster!,” emphasizing Bubbles’ irrationally anxious concept of black men as sexual hooligans who are all violently obsessed with her. But how could it be any different? The enforcement of race as a construct requires a delirious stream of around-the-clock narrative building. The racial construct is a fiction constantly being added to and broadened, like a new bible. It is a narrative that is created through symbols, through platitudes, and through stereotypes! To puncture a narrative of this scope, one must be vicious. And Darius, your writing is vicious, absurd, and animated by a wicked intelligence dedicated to ripping down the whole storyboard.

African philosopher named Achille Mnembe has referred to the persistence of the fetishizing of “blackness” and “race” as “the delirium of modernity.” And “the delirium of modernity,” is at the essence of Negrophobia's exasperated logic. Negrophobia uses delirious and phantasmagoric manifestations of racial stereotyping as a method of exposing the utter absurdities that racial ideology is built upon. Whereas Kierkegaard believed that “absurdism” was a useful artistic and literary technique for exposing the illogical nature of faith, you used literary absurdism for a much more singular purpose: exposing the illogical nature of using the concept of race as a way to distinguish social life and enforce power.

“Camera pulls back and reveals a monstrous, mammy-sized cookie jar of a woman with doughy animal features and crazed incandescent eyes,” you wrote. “Her nappy bleach-blond Afro is a crown of spiky thorns matted with sweat and splashed with splats of Day-Glo colors.” How can anyone mistake something so psychotically over-dramatized for a perpetuation of racist sentiment? It is clearly satire! Though it seems that more and more black artists are given access to the elite institutions of the arts, it is rarer and rarer that black artists of your complicated ideological viewpoint are allowed to speak at all. There’s a reason that filmmakers like Jordan Peele and Barry Jenkins are getting rich in Hollywood, and that is because their films are flattering the social consciousness of white Hollywood liberals or appealing to their white guilt in ressentiment.

What’s curious now is the way the expectations placed on black artists have been reversed. Postmodern fiction writer Ishmael Reed recently wrote a piece on his collaborator, the filmmaker Bill Gunn who directed the arthouse horror masterpiece Ganja and Hess, and about how Gunn was shunned by Hollywood because he wanted to make non-ideological films about black aesthetes. Instead, Hollywood wanted him to make films that functioned largely as “anti-black propaganda.” When Gunn refused, he was cut out of the industry almost entirely. But now, Darius, it is damn near impossible for black artists to portray black people as anything less than upstanding, moral people, reinforcing the left liberal notion that marginalization is inherently something to celebrate and closing the window on anything resembling complexity and humanity. Art is a reflection of the human psyche, without the darker impulses of man, there is no art! You Darius, you reveled in the grotesquerie and ugliness of contemporary life.

Kara Walker, for instance, an admirer of yours, suffered a fierce backlash after she won the Macarthur Genius grant for her silhouetted depictions of life on the plantation. The mostly black artists who went after her, like Betye Saar, were furious that Walker dared to depict anything other than black uplift! They even went so far as to say that Walker was pandering to the “white art establishment!” But who in their right mind can say that Walker’s brutality was pandering more than artists like Kehinde Wiley, whose only aim is to “rectify” the art historical canon. Wiley wants his black subjects to be worshipped and ogled in the way that the white subjects of Rubens or Caravaggio are.

But the logic of Wiley is fundamentally neoliberal. His quest to have his subjects accepted into the sphere of elite institutions is culturally analogous to the quest of neoliberalism to secure the elite status of some people of color at the expense of the many being left behind. That Wiley was asked to paint the post-presidency portrait of Barack Obama is oh so perfect! Obama’s symbolic victory as the first black president is used to mystify the reality of his presidency, in which hundreds of thousands of Americans, including black Americans, lost their homes, while Obama did his backers in Wall Street a solid and bailed their crook asses out! Wiley’s stately portrait of a hollow symbolic victory is in fact a hollow symbol of what passes for political progress in neoliberalism. As Walter Benn Michaels says, that is the “trouble with diversity,” that we learned to “love diversity” and “ignore inequality.”

What’s so disturbing about the efforts to censor you – to silence you, really – and Walker is that it narrows the window of acceptable content to which black artists are allowed to work within. Imagine David Lynch being told by white artists that he can’t depict anything other than “white uplift!” What so often masquerades as the ethos of emancipation is actually an assault on art itself! It is more RACIST than anti-racist! Why should any artist, black, white or otherwise, limit their fascinations, perversions, and fetishes to those which are deemed morally righteous! They shouldn’t Darius, and you sure didn’t! You did the opposite! You appropriated every taboo – every naughty, ugly idea that both black and white liberal artists deemed off the table – and sculpted those taboos into form.

You made all the right enemies! Right wingers! White liberal publishers! Amiri Baraka! You enraged them all! You suffered from being ahead of your time! You created an art that shattered the walls between truth and lies and amongst the rubble we saw how indistinguishable the two allegedly antithetical concepts really are. “Negrophobia is a work of fiction,” you write in the novel’s introduction, “Every word is true. Fuck you.” When everything you’re told is a lie, then every lie becomes the truth. They lie to us, Darius! But you told us the truth! You told us that the truth is there, buried in the LIES (oh how Freudian)! Negrophobia is a work of post-structuralist fiction that “deconstructs” the titanic narrative that has been constructed to validate the persistence of racial ideology. It is, without a shred of a doubt, a masterpiece.

Had Negrophobia been published now, it would have resulted in outrage, no doubt. But it also would have benefitted from contemporary discourses about the hollowness of neoliberalism’s absorption of identity politics. You were just too early! Tragically, Negrophobia remains your one published work of fiction (if I ever start a publishing imprint, you will be the first writer that I harass to get new work out of, I promise). You expected this, it seems, you even told BOMB Magazine that “if you were concerned about the repercussions” you wouldn’t be doing your job “as a satirist.” And as Karl Marx once said, “Lacking its own ingenuity, the parasite fears the visionary. What it cannot plagiarize, it seeks to censor. What it cannot regulate, it seeks to ban.” You terrified the parasites, Darius, but your artistic genius is preserved, in Negrophobia.

NOTE: this essay is connected to my my essay series for the Quarterless Journal, ‘Conversations in Trolls’

Hanna Liden ‘Self-Portrait with Rat’ (2010)

An Ode to Artist Hanna Liden: Transcendence of Urban Decay Through The Piercing of Unreality

The New York art world, post-9/11, had serious “end of Rome,” late empire decadence vibes. Copious amounts of heroin, alcohol, ketamine and cocaine were fueling the late night exploits of some of the industry’s fastest rising stars. Dash Snow. Ryan McGinley. Dan Colen. It’s hard not to look back on this era of artists and the media that made them stars (early VICE, the much missed Index Magazine, and others) as the sales pitch of an apolitical and tragically bourgeois lifestyle brand. Dash Snow was literally the ne'er-do-well black sheep of the de Menil family fortune, and the mythos that he had constructed around his persona; that of the drug addict bohemian rich kid reject; was every bit as fascinating as his art (I will add here that I love Snow’s work, and his mythos, and find much of the common criticism of it to be annoying and puritanical).

It’s not that Snow’s art wasn’t interesting. It was, certainly. His work manifested the dejection of a generation about to realize that it was born into a failed state. There was nothing left to rage against because the neoliberal ethos had been so internalized into the system that no amount of protest could ever mount anything resembling a structural threat to it. Camille Paglia tells us that Oscar Wilde was a “late romantic elitist, in the Baudelarian manner.” Dash Snow then was a “late capitalist elitist, in the Baudelarian manner.” Snow was utterly apolitical and dedicated to nothing but the assault of mainstream sensibilities and a Wildean avoidance of work ethic (a perfectly acceptable artist ethos and one ever more laudable than the litany of faux social justice minded art we see today). Born rich, Dash rejected bourgeois civility and misery and relished the fall of the empire and the collapse of the social code. Fair enough. Dash’s art loudly screamed: “Fuck it.” Get cash rich. Get wasted. Shoot all the pleasure into your veins and die before you become another fat rich dinosaur attending “philanthropic” galas and fundraisers while getting your picture taken alongside Rosie O’Donnell and Bill Clinton. And Dash did; die that is. Tragically young and just at the moment that his body of work was really starting to coalesce into something expressively potent.

Dash Snow ‘Polaroid Wall’ (2005)

Snow died. McGinley went straight and capitalized on the frenetic narcosis of his early career and parlayed it into a highly lucrative if aesthetically inoffensive and somewhat banal career in commercial portraiture and the production of many images of frolicking bone thin, androgynous youths. And that’s the point: when an art culture sells a lifestyle, it is easily commodified as a lifestyle brand. The commodification of McGinley, VICE, and the broader early ‘00s New York art world has overshadowed the genuine creative talents and art historical importance of some of its best artists: Snow, his ex-wife Agathe Snow, and others among them.

It’s not like Dash was the first heroin and crack indulgent artist. Artists like Alex Bag and Tracey Emin have been open about their past weaknesses for narcotics, and yet, it’s not the first thing that comes to mind when you think about their roles in the art world. With Dash and his crew, it is. It’s the excess baggage of living up to your self-constructed mythology. “In much of what has been written about Snow, the prose collapses into a journalistic bile of voyeurism and disavowal driven by conflicting desires to appear “with it” and yet retain a judgmental distance,” wrote critic David Rimanelli (a close friend and an admirer of Snow’s, also one of the few ArtForum writers whose work I regularly look forward to reading and almost never makes me want to hurl, but that’s neither here nor there).

Hanna Liden early work from 2004

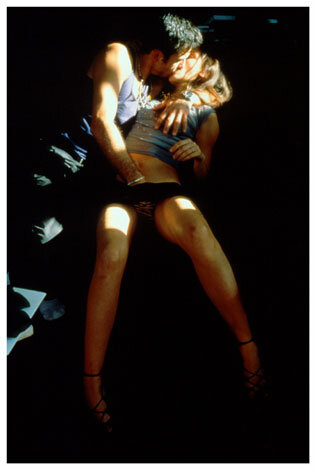

With this long-winded intro out of the way, allow me to get to an artist whose work I have loved and have wanted to write about for a long time. New York-based artist Hanna Liden was friends with Snow, McGinley, Colen and the others (in fact, Liden discovered Snow’s body in the summer of 2009, alongside Snow’s girlfriend Jade Berreau), and most likely indulged in and enjoyed the legendary decadence of that early millennium scene. But Liden, unlike Snow and McGinley especially, never made art that exploited the burnout bohemian lifestyle. Liden’s work — primarily rooted in photography and sculpture — is infinitely deeper, more personal, and more expressive than the work that was made by her artistic comrades. While Snow and McGinley produced documentarian photographs of their friends and collaborators engaged in degenerate, narcotized and coke stimulated unfulfilling acts of sexual emptiness (lots of heroin being shot with blow jobs being performed in the back of the frame, lines being snorted off of hard cocks, and so forth), Liden’s earliest notable art presented imagery that was simultaneously more thematically classical (nudes against nature) AND connected to an eerie and mystical force beyond the narrowly urban confines of downtown Manhattan.

Holland Cotter of the New York Times remarked that Hanna Liden’s earliest images were like “coven-like counterparts to the campers in Justine Kurland’s staged photographs of 1960s-style utopian communities.” I see these images as less a counterpart to Kurland’s work than a rejection of it. Liden’s work has long functioned as a bold rejection of art world trends, hegemonies, and orthodoxies.

Francisco de Goya ‘Witch’s Sabbath’ (1978)

The early-’00s art world sought after and rewarded the feminist striving in the work of artists like Kurland, or the bad boy libidnal catharsis found in the work of artists like Snow. That polarity seems to define the aesthetics of the era. Kurland’s work is directly connected to the neoliberal dilution of feminism that equated personal cultural success and upwards mobility with some kind of real material progress for the masses (despite all evidence pointing to this being a shallow and self-serving engagement with politics). Dash and McGinley, on the other hand, responded to the rot of post-Reaganite America with a holy sigh of intoxicating apathy, almost like they looked at what Fukuyama called “The End of History” and responded by getting stoned and rich (“as fuck”).

Liden’s work is infinitely more connected to artists like Blake, Goya, and Munch than those aforementioned that she worked alongside contemporaneously. It attempts to grapple with the chaos of reality by exercising control over nature through a present day occultist mysticism. Liden enjoyed urban life, but her art only referenced it so much as it offers something beyond it. Her art exits the simulacrum and peaks through the red curtains of the black lodge double exposed onto the image of bleak, sublime nature, coming into visual contact with the unnamable. Through the forest is mystery. As Rene Magritte once said: “Art evokes the mystery without which the world would not exist.” Liden’s early work, and much of her art thereafter, has functioned as an exorcism of the spiritual rot of late capitalism and a channeling of the occulted essence of pure artistic creation.

Jean Rollin ‘Lips of Blood’ (film still) (1975)

Liden’s early work was ruthlessly committed to a singular aesthetic that had little formal precedent in the postmodernist generation that defined the New York art world in the decades before her arrival to the city. The work gestures towards the aforementioned historical painters, the cosmic pessimism of Lovecraft, the occult crackpot theorizing of Colin Wilson, Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, and especially the surrealist “fantastiqué” horror cinema of the late French filmmaker Jean Rollin (Liden has also cited Eraserhead, A Nightmare on Elm Street, and Tetsuo: The Iron Man, as major influences). It’s striking how similar that first Liden series looks next to Rollin’s gorgeously macabre film stills (Rollin is a filmmaker best experienced through film stills, in my opinion). Her images, like his, lean into the horror aesthetic but are mystically illuminated by an ethereal presence of possessed eloquence. Liden’s 2004 photograph, aptly titled Love and Death, depicts two nude women against barren, dead nature: one looks through a magnifying glass while the scarf draped around her neck and down her back is grasped by the woman behind her, hidden beneath a skull mask, like the comforting embrace of death itself. The image is eerily similar in both thematic content and aesthetic to stills from Rollin’s 1975 film Lips of Blood; the vampiric feminine… Sex, death, life and decay expelled in ritualistic energy and synergistic movement.

Liden once said that her fanatical obsession with religious rites stems from her largely atheist upbringing in Scandinavia – A landscape bathed in nature in all its sublime beauty and cosmic brutality. Scandinavia's overwhelming ominosity has long been explored by the country’s artists from Munch to Darkthrone… Artists that harness the primal scream of deific nature. Liden’s fascination with the religious rite is purely fetishistic, or in other words, artistic. Freed from religious devotion or theological rigor, Liden visualizes the rite as one of violent and sexual catharsis. Her subjects aren’t “practicing religion” so much as they are shedding themselves of the modern and embracing the primordial. Her subjects dance and pose under the moonlight or dimly sunlit skies, shrouded in chthonic overgrowth. The images hint at the Freudian uncanny in their blending of art historical formality with the fashions not atypical to contemporary generations (when they aren’t naked, there are hoodies, deconstructed jumpers, tight jeans, and so on). And this is where the work gets so deliciously ambiguous. There is no clear narrative in these images, but there is a profound implication of one.

Hanna Liden ‘Love and Death’ (2004)

The contemporary horror fiction writer and theorist Gary J Shipley said that, “Reality is horror – it eats people like a carnivorous fog – a construct so diabolical that man has been unwittingly cajoled into adorning the effervescence of his dreams and his fantasies with costumes of malleable terror.” What Shipley means here is that the horror of our nightmares is merely what online political actors would now call “a cope.” Liden’s images are uncanny, spooky, and saturated with horror. But they aren’t “horror,” per se. The erotic rite depicted by Liden is an escape from the horror of contemporary life. This is where Liden does share some overlap with her late friend Snow. Both artists were/are fascinated in ritual, it’s just that Snow’s rituals are common and banal; rituals of decadence and drug induced frenzy. Liden’s rituals attain psychoactivity and transcendence through the expulsion of late capitalist anxiety and the piercing of the ethereal. Liden’s ritual is more difficult to attain. It can’t be achieved through the intravenous injection of brown and white powders or the imbibing of bitter liquors. It must be conjured. Liden’s art rejects Dionysian decadence in favor of the ancient methods of the witch and the mystic. Nevertheless, Liden and Snow’s art is united against the alienating forces of liquid modernity.

And though Liden’s early work’s aesthetics were undeniably original in the early 2000s, it’s clear that younger artists have internalized the visual language of her images to some degree. In 2020, the uncanny is everywhere. Contemporary art is soaked in the signifiers of horror, the occult, and dark magic. Filmmaker and horror fiction writer Clive Barker once said that, “Horror fiction shows us that the control we have is purely illusory, and that every moment we teeter on chaos and oblivion.”

Hanna Liden ‘Eternal Flame’

Liden’s work, in some sense, feels connected to the social anxiety that emerged in the wake of 9/11 and was experienced most viscerally by New Yorkers living in proximity to Ground Zero; the implication of horror in her work functions as an attempt to harness and control the terror of reality. Her early work is a macabre ritual that attempts to both exit and cope with existential dread. The existential dread of contemporary life has never been more pronounced than it is in 2020: stunning inequality, mass joblessness, rapid shifts in media narrative, the “radlibs” subsuming left politics in reductionism, and a literal plague. It should be no surprise that contemporary artists are, like Liden was in the early 2000s, creating horror-adjacent art that addresses the incoherence and dreadful angst of life in late capitalism, even when the work drifts into camp aesthetics.

The sculptural works of Dan Herschlein and the Croatian art duo Tarwuk trade in an austerely horror soaked style that mimics the peculiar alienation that gnaws at us in the back of our minds. Not shocking terror, but muted, persistent disquietude. Artists and curators Paul Gondry and Shelby Jackson have created an entire space – the Brooklyn gallery 15 Orient – dedicated to work that similarly deals with this complex rendering of occasionally occult-leaning, always macabre aesthetics (I’ll also recommend the duo’s excellent Chronicles of Shongle video project). Liden’s work, though dreadfully under appreciated and written about, has reverberated throughout the art world as a thematic and visual influence for decades.

Dan Herschlein ‘I Sing a Happy Song in my Wake’ (2019)