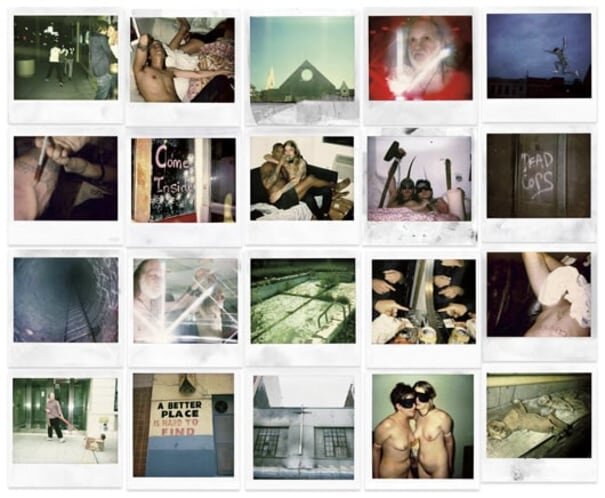

The New York art world, post-9/11, had serious “end of Rome,” late empire decadence vibes. Copious amounts of heroin, alcohol, ketamine and cocaine were fueling the late night exploits of some of the industry’s fastest rising stars. Dash Snow. Ryan McGinley. Dan Colen. It’s hard not to look back on this era of artists and the media that made them stars (early VICE, the much missed Index Magazine, and others) as the sales pitch of an apolitical and tragically bourgeois lifestyle brand. Dash Snow was literally the ne'er-do-well black sheep of the de Menil family fortune, and the mythos that he had constructed around his persona; that of the drug addict bohemian rich kid reject; was every bit as fascinating as his art (I will add here that I love Snow’s work, and his mythos, and find much of the common criticism of it to be annoying and puritanical).

It’s not that Snow’s art wasn’t interesting. It was, certainly. His work manifested the dejection of a generation about to realize that it was born into a failed state. There was nothing left to rage against because the neoliberal ethos had been so internalized into the system that no amount of protest could ever mount anything resembling a structural threat to it. Camille Paglia tells us that Oscar Wilde was a “late romantic elitist, in the Baudelarian manner.” Dash Snow then was a “late capitalist elitist, in the Baudelarian manner.” Snow was utterly apolitical and dedicated to nothing but the assault of mainstream sensibilities and a Wildean avoidance of work ethic (a perfectly acceptable artist ethos and one ever more laudable than the litany of faux social justice minded art we see today). Born rich, Dash rejected bourgeois civility and misery and relished the fall of the empire and the collapse of the social code. Fair enough. Dash’s art loudly screamed: “Fuck it.” Get cash rich. Get wasted. Shoot all the pleasure into your veins and die before you become another fat rich dinosaur attending “philanthropic” galas and fundraisers while getting your picture taken alongside Rosie O’Donnell and Bill Clinton. And Dash did; die that is. Tragically young and just at the moment that his body of work was really starting to coalesce into something expressively potent.

Dash Snow ‘Polaroid Wall’ (2005)

Snow died. McGinley went straight and capitalized on the frenetic narcosis of his early career and parlayed it into a highly lucrative if aesthetically inoffensive and somewhat banal career in commercial portraiture and the production of many images of frolicking bone thin, androgynous youths. And that’s the point: when an art culture sells a lifestyle, it is easily commodified as a lifestyle brand. The commodification of McGinley, VICE, and the broader early ‘00s New York art world has overshadowed the genuine creative talents and art historical importance of some of its best artists: Snow, his ex-wife Agathe Snow, and others among them.

It’s not like Dash was the first heroin and crack indulgent artist. Artists like Alex Bag and Tracey Emin have been open about their past weaknesses for narcotics, and yet, it’s not the first thing that comes to mind when you think about their roles in the art world. With Dash and his crew, it is. It’s the excess baggage of living up to your self-constructed mythology. “In much of what has been written about Snow, the prose collapses into a journalistic bile of voyeurism and disavowal driven by conflicting desires to appear “with it” and yet retain a judgmental distance,” wrote critic David Rimanelli (a close friend and an admirer of Snow’s, also one of the few ArtForum writers whose work I regularly look forward to reading and almost never makes me want to hurl, but that’s neither here nor there).

Hanna Liden early work from 2004

With this long-winded intro out of the way, allow me to get to an artist whose work I have loved and have wanted to write about for a long time. New York-based artist Hanna Liden was friends with Snow, McGinley, Colen and the others (in fact, Liden discovered Snow’s body in the summer of 2009, alongside Snow’s girlfriend Jade Berreau), and most likely indulged in and enjoyed the legendary decadence of that early millennium scene. But Liden, unlike Snow and McGinley especially, never made art that exploited the burnout bohemian lifestyle. Liden’s work — primarily rooted in photography and sculpture — is infinitely deeper, more personal, and more expressive than the work that was made by her artistic comrades. While Snow and McGinley produced documentarian photographs of their friends and collaborators engaged in degenerate, narcotized and coke stimulated unfulfilling acts of sexual emptiness (lots of heroin being shot with blow jobs being performed in the back of the frame, lines being snorted off of hard cocks, and so forth), Liden’s earliest notable art presented imagery that was simultaneously more thematically classical (nudes against nature) AND connected to an eerie and mystical force beyond the narrowly urban confines of downtown Manhattan.

Holland Cotter of the New York Times remarked that Hanna Liden’s earliest images were like “coven-like counterparts to the campers in Justine Kurland’s staged photographs of 1960s-style utopian communities.” I see these images as less a counterpart to Kurland’s work than a rejection of it. Liden’s work has long functioned as a bold rejection of art world trends, hegemonies, and orthodoxies.

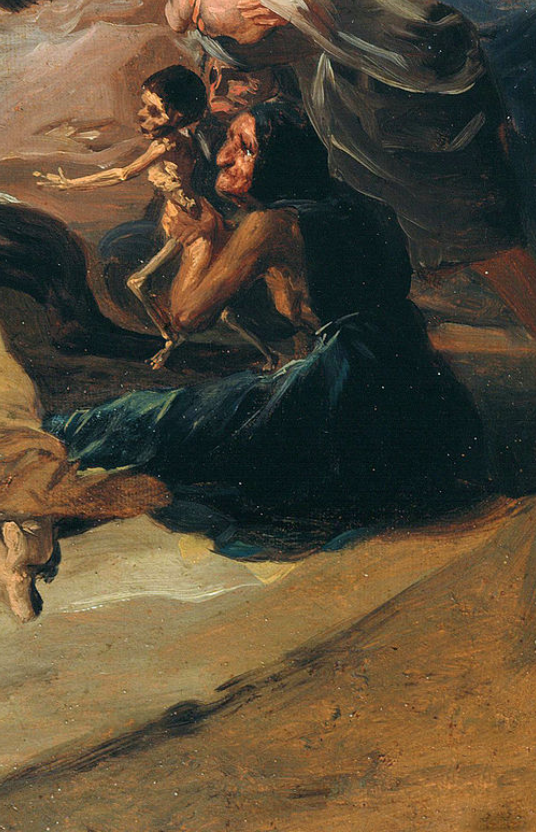

Francisco de Goya ‘Witch’s Sabbath’ (1978)

The early-’00s art world sought after and rewarded the feminist striving in the work of artists like Kurland, or the bad boy libidnal catharsis found in the work of artists like Snow. That polarity seems to define the aesthetics of the era. Kurland’s work is directly connected to the neoliberal dilution of feminism that equated personal cultural success and upwards mobility with some kind of real material progress for the masses (despite all evidence pointing to this being a shallow and self-serving engagement with politics). Dash and McGinley, on the other hand, responded to the rot of post-Reaganite America with a holy sigh of intoxicating apathy, almost like they looked at what Fukuyama called “The End of History” and responded by getting stoned and rich (“as fuck”).

Liden’s work is infinitely more connected to artists like Blake, Goya, and Munch than those aforementioned that she worked alongside contemporaneously. It attempts to grapple with the chaos of reality by exercising control over nature through a present day occultist mysticism. Liden enjoyed urban life, but her art only referenced it so much as it offers something beyond it. Her art exits the simulacrum and peaks through the red curtains of the black lodge double exposed onto the image of bleak, sublime nature, coming into visual contact with the unnamable. Through the forest is mystery. As Rene Magritte once said: “Art evokes the mystery without which the world would not exist.” Liden’s early work, and much of her art thereafter, has functioned as an exorcism of the spiritual rot of late capitalism and a channeling of the occulted essence of pure artistic creation.

Jean Rollin ‘Lips of Blood’ (film still) (1975)

Liden’s early work was ruthlessly committed to a singular aesthetic that had little formal precedent in the postmodernist generation that defined the New York art world in the decades before her arrival to the city. The work gestures towards the aforementioned historical painters, the cosmic pessimism of Lovecraft, the occult crackpot theorizing of Colin Wilson, Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, and especially the surrealist “fantastiqué” horror cinema of the late French filmmaker Jean Rollin (Liden has also cited Eraserhead, A Nightmare on Elm Street, and Tetsuo: The Iron Man, as major influences). It’s striking how similar that first Liden series looks next to Rollin’s gorgeously macabre film stills (Rollin is a filmmaker best experienced through film stills, in my opinion). Her images, like his, lean into the horror aesthetic but are mystically illuminated by an ethereal presence of possessed eloquence. Liden’s 2004 photograph, aptly titled Love and Death, depicts two nude women against barren, dead nature: one looks through a magnifying glass while the scarf draped around her neck and down her back is grasped by the woman behind her, hidden beneath a skull mask, like the comforting embrace of death itself. The image is eerily similar in both thematic content and aesthetic to stills from Rollin’s 1975 film Lips of Blood; the vampiric feminine… Sex, death, life and decay expelled in ritualistic energy and synergistic movement.

Liden once said that her fanatical obsession with religious rites stems from her largely atheist upbringing in Scandinavia – A landscape bathed in nature in all its sublime beauty and cosmic brutality. Scandinavia's overwhelming ominosity has long been explored by the country’s artists from Munch to Darkthrone… Artists that harness the primal scream of deific nature. Liden’s fascination with the religious rite is purely fetishistic, or in other words, artistic. Freed from religious devotion or theological rigor, Liden visualizes the rite as one of violent and sexual catharsis. Her subjects aren’t “practicing religion” so much as they are shedding themselves of the modern and embracing the primordial. Her subjects dance and pose under the moonlight or dimly sunlit skies, shrouded in chthonic overgrowth. The images hint at the Freudian uncanny in their blending of art historical formality with the fashions not atypical to contemporary generations (when they aren’t naked, there are hoodies, deconstructed jumpers, tight jeans, and so on). And this is where the work gets so deliciously ambiguous. There is no clear narrative in these images, but there is a profound implication of one.

Hanna Liden ‘Love and Death’ (2004)

The contemporary horror fiction writer and theorist Gary J Shipley said that, “Reality is horror – it eats people like a carnivorous fog – a construct so diabolical that man has been unwittingly cajoled into adorning the effervescence of his dreams and his fantasies with costumes of malleable terror.” What Shipley means here is that the horror of our nightmares is merely what online political actors would now call “a cope.” Liden’s images are uncanny, spooky, and saturated with horror. But they aren’t “horror,” per se. The erotic rite depicted by Liden is an escape from the horror of contemporary life. This is where Liden does share some overlap with her late friend Snow. Both artists were/are fascinated in ritual, it’s just that Snow’s rituals are common and banal; rituals of decadence and drug induced frenzy. Liden’s rituals attain psychoactivity and transcendence through the expulsion of late capitalist anxiety and the piercing of the ethereal. Liden’s ritual is more difficult to attain. It can’t be achieved through the intravenous injection of brown and white powders or the imbibing of bitter liquors. It must be conjured. Liden’s art rejects Dionysian decadence in favor of the ancient methods of the witch and the mystic. Nevertheless, Liden and Snow’s art is united against the alienating forces of liquid modernity.

And though Liden’s early work’s aesthetics were undeniably original in the early 2000s, it’s clear that younger artists have internalized the visual language of her images to some degree. In 2020, the uncanny is everywhere. Contemporary art is soaked in the signifiers of horror, the occult, and dark magic. Filmmaker and horror fiction writer Clive Barker once said that, “Horror fiction shows us that the control we have is purely illusory, and that every moment we teeter on chaos and oblivion.”

Hanna Liden ‘Eternal Flame’

Liden’s work, in some sense, feels connected to the social anxiety that emerged in the wake of 9/11 and was experienced most viscerally by New Yorkers living in proximity to Ground Zero; the implication of horror in her work functions as an attempt to harness and control the terror of reality. Her early work is a macabre ritual that attempts to both exit and cope with existential dread. The existential dread of contemporary life has never been more pronounced than it is in 2020: stunning inequality, mass joblessness, rapid shifts in media narrative, the “radlibs” subsuming left politics in reductionism, and a literal plague. It should be no surprise that contemporary artists are, like Liden was in the early 2000s, creating horror-adjacent art that addresses the incoherence and dreadful angst of life in late capitalism, even when the work drifts into camp aesthetics.

The sculptural works of Dan Herschlein and the Croatian art duo Tarwuk trade in an austerely horror soaked style that mimics the peculiar alienation that gnaws at us in the back of our minds. Not shocking terror, but muted, persistent disquietude. Artists and curators Paul Gondry and Shelby Jackson have created an entire space – the Brooklyn gallery 15 Orient – dedicated to work that similarly deals with this complex rendering of occasionally occult-leaning, always macabre aesthetics (I’ll also recommend the duo’s excellent Chronicles of Shongle video project). Liden’s work, though dreadfully under appreciated and written about, has reverberated throughout the art world as a thematic and visual influence for decades.

Dan Herschlein ‘I Sing a Happy Song in my Wake’ (2019)

Liden’s work would shift following her earlier nature nudes; she stopped leaving the city so much and began opting to produce images within her studio. That said, her next series of images would ultimately continue with earlier themes of transcendence, spiritual escape, and commune with that which lies beyond. Liden’s sculptural still-life photographs depict rows of formerly lit, blown out gothic candles in unison, emitting ghastly forms of smoke that float up and out of the frame. Shot entirely against mostly black studio backdrops and alternating between harshly saturated colors (blood red, yellow), the images exude a compressed paganism. The photos are meant to reference 17th Century Dutch artist Willem Kalf’s iconic vanitas still-life paintings that, like Liden’s images, drift back and forth between reality and a dimension unseen (death maybe, something else possibly). Devoid of the naked bodies, foreboding natural landscapes, and macabre visual signifiers of her early images, Liden imbues the images with a harnessed phantasmic atmosphere. Liden has told an interviewer that she doesn’t believe in the supernatural “at all.” And yet, her work attempts to call forth the supernatural, nonetheless. Her art is a suspension of disbelief, that is the source of its power.

Looking at these still-life images – they are elegant and dense, Dan Colen has remarked that they work better as sculptural pieces than flat photographs – is like closing your eyes after snorting a substantial line of Ketamine; first, you sink back into the dark void of your mind, and then once suffused into the darkness your subjectivity/spirit exits the physical trappings of the body as it slowly drifts through the walls of perception and into the nether realms of the K-hole. These images are a threshold between Borgesian parallel universes; the surface of the photograph is the looking glass through which you can travel.

After Willem Kalf ‘Still Life with Nautillus Cup’ (1665)

Hanna Liden ‘Blown Out Candles (Blood’

Liden’s early work connected to the beyond through pagan rituals, this series connected to it through the seancé. As always, Liden’s work relates to the urban lifestyle in its attempts to escape from it by using an unseen mystic power, magic black as night, to slip into a reality unknown. Without action or movement, Liden still achieves otherworldliness in these still-lives by suffusing them with vague unheimlich and a contemplative quality that the filmmaker and critic Paul Schrader would call “transcendent style.” Hanna Liden is the only downtown NYC artist of the early 2000s to achieve such an aesthetic.

In more recent years, Liden started to deal more directly with the signifiers and objects of the cityscape that she had by then inhabited for decades. Much of these works, sculptures mainly, are fascinatingly melancholic and subtly beautiful. Liden, unwilling to divorce herself entirely from her intuitive connection to occultist themes, reimagined the cityscape as one equally capable of tapping into the collective unconscious. At an exhibition at Maccarone Gallery from 2011 entitled Out of My Mind, Back in 5 Minutes, Liden presented discarded delivery bags assembled atop one another as the totems of the liquid modern urban landscape… They are assembled detritus of the solar anus of the overworked, over-stressed, and money-strapped citizens of the concrete jungle. What’s enduringly interesting about this work is Liden shifts the focus of her art from desolate nature to the chaotic city, but her inherently Scandinavian connection to the ethereal still bleeds into the work. Less successful, unfortunately, is Liden’s public “bagel vase sculptures'' that depict the city’s famed breakfast snacks stacked atop one another. The work feels kitsch – not camp, as her early horror-leaning works often were to thrilling effect – and dilutes her body of work. Liden’s art suffers when it roots itself entirely within the material. It’s not who she is. She is an atheist spiritualist; an artist who does not believe, but attempts to imagine a space in which belief in something beyond is possible.

Hanna Liden ‘Delivery’ (2011)

“But the world as it stands is no narrow illusion, no phantasm, no evil dream of the night;” writes Henry James in Theory of Fiction. “We wake up to it, forever and ever; we can never forget nor deny it nor dispense with it.” Liden’s work is a harsh acknowledgement of the apocalyptic spiritual rot of life in late modernism. Though its themes are immaterial, her art is in persistent dialog with the material. While looking at Snow’s old polaroids, we stew in nostalgia for an era of decadence that rose in the face of late capitalist exhaustion and defeat. It’s gone. We can’t have it back. But Liden shows us a space of unreality that is eternal. Though she’s not sure it exists at all, she allows for the possibility that it’s there, and that through ritual and rite we can enter it, and bathe in its enlightenments, luxuriate in its insights impossible to give language to. She’s perhaps the only Schopenhauerian artist of her “scene.” Schopenhauer believed that art must be a refuge from the material world of “strife and will.” Liden lets us take refuge in something strange but beautiful, difficult to articulate but omnipresent.

Hanna Liden ‘Black Sabbath’ (2003)