Before 20th Century Spanish-American artist Federico Castellón moved with his family to Brooklyn, he lived in Barcelona during the height of the General Strike of 1919. A Barcelona hydroelectric plant had cut the wages of its workers, who responded with a massively successful worker walkout with over 100,000 participants. The strike’s cultural impact rapidly ricocheted, and electric and textile employees all followed suit by walking off duty. Eventually, the Catalan economy was crippled, and the workers earned the world’s first guaranteed eight hour work day. But when the government refused to release imprisoned protesters, the organizing persisted.

The capitalists and the Barcelona government responded with brutality and bloodshed. The rising dullard of a dictator Primo de Rivera banned all activist and anarchist organizations in the country, and organizers were murdered and imprisoned. The anarchists that remained on the streets resorted to violence, bombing targeted locations and assassinating prominent political figures.

Castellón vividly remembered the carnage. He recalled to an interviewer a day when was a boy: he and his brothers had lied to their mother about going to see a movie. They never went. Their lie turned out to be a blessing when the movie theater that their mother thought they were in attendance at was bombed, killing dozens. Their mother spent the afternoon agonizing over the deaths of her sons. When her sons showed up for dinner, she beat them, overwhelmed by the simultaneous emotions of relief, horror, and anger. When his family left for the United States he found himself alienated and alone. Barcelona, despite its bloodshed and political malaise, was home. America — safe and banal — was torturous. Castellón observed reality as a grid of interlocking paradoxes. Comfort is violence. Violence is love. And love? Oh boy. Love is sheer hell (wouldn’t you agree, Federico?).

“My life was miserable as I remember it as a child here in the States,” said Castellón. “I'd go out in the street and just hang around and watch the other kids play for ten minutes and back in the house and draw again. It seemed the only activity that I could pursue and save my sanity, somehow.”

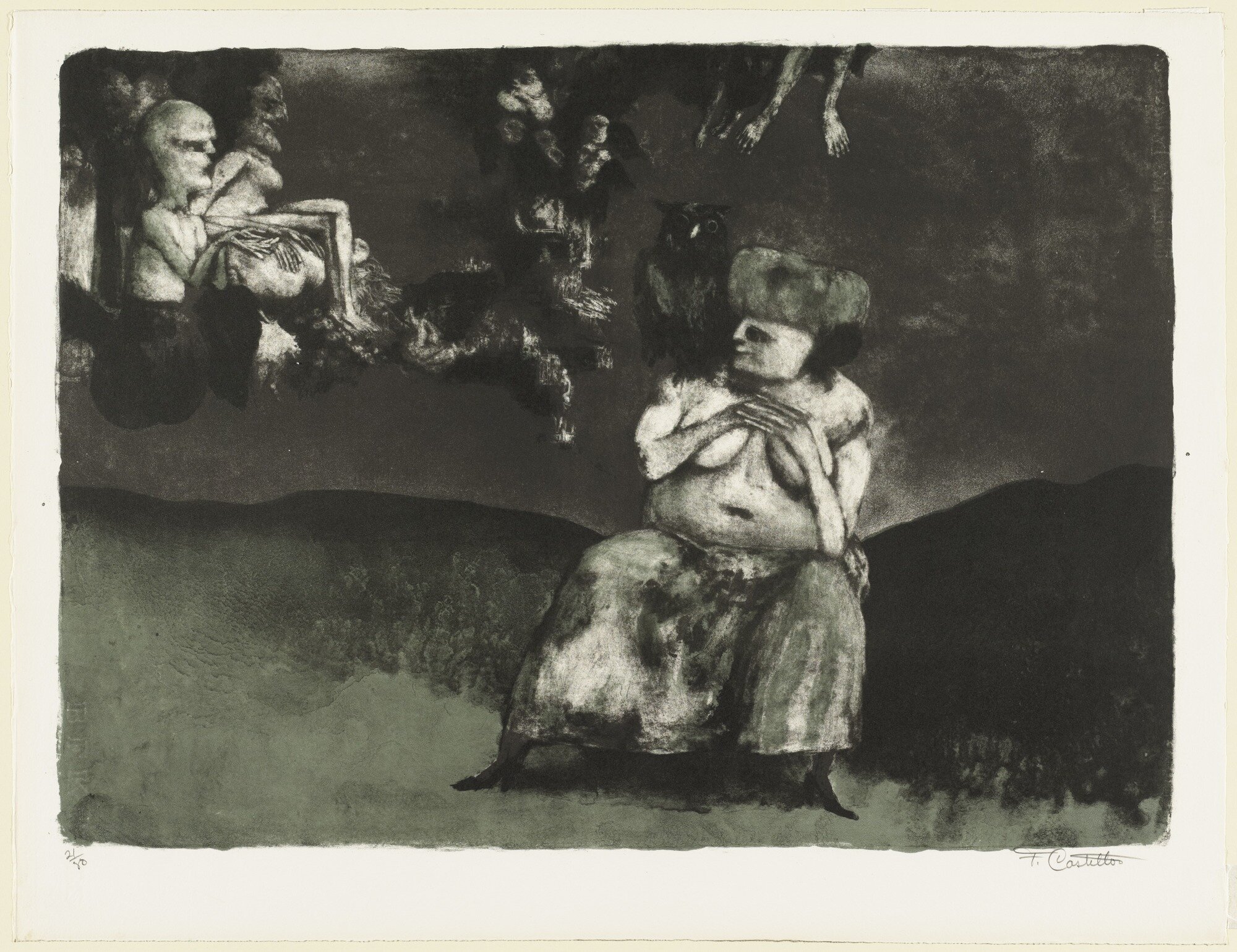

Federico Castellón, ‘Erotica,’ (1970)

Castellón’s art would appear to have its genesis here. His images — disturbing, pregnant with perverse mystery — connect human experience’s banalities to its most abject brutalities. “No mom, we weren’t at the movies, our flesh hasn’t been incinerated.” Often considered a proto-Surrealist, Castellón wasn’t just looking to evoke the unconscious mind and his own interiority. His fantastical imagery was still connected to lived human experience and unearthed a Lacanian real beneath the veneers of the symbolic order, the spectacle, and the clean veneer of mondernist reality.

His images are defined by a kind of depersonalization disorder. It’s reality seen from outside your body. Montana becomes Oz. An interpretation of a dream. That reality is modernism. The lie of modernism is progress. And Castellón was one of modernist art’s chief modernist critics and skeptics.

“Many artists have been drawn to things dark and fantastic,” says critic Annisa Liu. “But few have probed the human psyche with the insight and truthfulness found in these images.”

Though it might be surprising when one first comes across the macabre splendor of Castellón’s muted color palette, disembodied human forms, and vivid eroticism, it was Mexican muralist Diego Rivera that plucked Castellón from obscurity when the artist was still a teenager living in Brooklyn.

What did you see in young Federico, Diego? You, Diego, were a storyteller, at essence. A communist, you sought to vivify the brutal conditions endured by the working class and the violence that erupted from the struggle for emancipation. What drew you to Castellón’s uncanny visual realms? In Dostoyevsky’s Demons, Dostoyevsky personifies the malicious intentions of the novel’s politically radicalized characters as demons, or ghosts, or devils. Castellón’s work functions in a similar way. If Rivera tells the story, then Castellón gives life to the evils that propelled the story. Evil, mischievousness, impotent rage. In Castellón’s work, intentions are living beings. Monstrous beings. “I can’t afford this,” you think to yourself. “Steal it,” says the demon grinning lasciviously. These private moments of inner experience take life in Castellón’s art, and they are embodiments of the faux utopianism that characterized modernism and modernist art.

Federico Castellón ‘Untitled’ (1919)

William Blake ‘St. Matthew’ (1799)

Castellón was interested in art as mysticism. He obsessed over the gods in Michaelangelo, and the demi-gods in El Greco and William Blake. Castellón exists on this continuum. As religion continues to erode as a value system, so does mystic art. Castellón is a mystic for a god-less culture. A druid for a society that has murdered its gods. “Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?” asks Nietzsche.

Castellón’s art castigates us for daring to live in a god-less world. The mysticism that courses through his work is decayed. It’s been dead for some time, and Castellón forces us to confront what we’ve done — through technology, through capitalism, through science — to our bedrock traditions and modes of belief.

Castellón is one of those rare 20th Century modernist artists that treated modernism as a disease. The modernist virus that had engulfed the land in false promises of hope and utopia. That rejection of the promises of modernism — a rejection that has been vindicated with the slow, persistent disintegration of social life that characterized globalization and the eventual destruction of the safety net in the contemporary West — introduced an artistic nihilism that operated in defiance of the utopian ideal of modernist thinking. Francis Bacon. Antonin Artaud. HP Lovecraft. Castellón’s visual skepticism of the 20th Century lent his work a bleakness that allows its impact to endure. One detects through the timeline of his work that he would even more disdainful of the prevailing ideology as society moved forward. His images got increasingly bleak, culminating with the ferociously perverted and psychotic Erotica lithographs of the early 1970s. Humanoid forms fucking and murdering each other, wrapped in bandages and warding off death. Castellon’s art is like the ideology sunglasses that Zizek reveres in John Carpenter’s They Live!. Put on the sunglasses, or look at the lithograph, and you’ll see the alien plot for world domination.

As Michel Houellebecq writes about Lovecraft in his literary analysis of the weird fiction pioneer: “Life is painful and disappointing. It is useless, therefore, to write new novels. We generally know where we stand in relation to reality and don’t care to know anymore.” What does this mean to you, Federico? The pain and uselessness of life must have been made abundantly clear to you when you were a child in Spain, trekking through the city with the smell of melted flesh of bombing victims illustrating your journeys to the cinema. What did the promises of modernism mean to you? Very little, I’d wager. But what do I know?

Federico Castellón ‘Edgar Allan Poe’s The Mask of Red Death’

There is a hauntological dimension at play in Castellón’s art. It mourns for gods, for mysticism, and for belief. But the gods have been replaced by their animated corpses; by us. Made in god’s image, but material. Rotting. Ephemeral, and in a persistent state of decomposition. We might look like gods according to the scriptures, but we are not gods. Consider an untitled lithograph from 1939. In it, a woman is bound to a chair. bondage style. Her back is towards us, and she looks over her head. Behind her, is a distended human form — the head sticking out of the flesh of the chest, no neck — that has its legs draped over the seated woman, attempting to float upwards, or so it seems. A human attempting to wield the power of a god. A human attempting the power of a god, and abjectly failing. My Federico, you surely had a lethal sense of humor.

Castellón’s most stunning series of works is a block of lithographs that the artist made for a re-print of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Mask of Red Death. If you haven’t read the book, I’ll briefly summarize it as a novella in which , against a backdrop of plague and mass death, a prince goes to a gathering of the wealthy elite — a celebration and a toast amongst those living as the new gods — while a mysterious figure cloaked in a red mask (Eyes Wide Shut, anyone?) makes his way through the rooms, stalking the guests and imbuing the proceedings with an uncanny and unwelcome atmosphere. The prince dies when he finally confronts this figure. The allegory, as is often the case with Poe, is clear: men cannot outpace death. Progress, technology, power, all futile. Dead ends.

Federico Castellón ‘The Alchemist Searches for the Philosopher’s Stone and the Elixir of Life’

Castellón’s lithographs are tinted in discolored greens and blues, evoking an aura of sickliness. Castellón depicts numerous human figures engaged in decadent, lewd, or banal acts, erstwhile specters of death and demonic malfeasance enter the frames of the canvases and skulk around the figures’ peripheries. In one of my personal favorites, a morbidly obese man sitting in a chair realizes that several floating specters are behind him, and he meekly covers the flab of his fat chest, his “bitch tits,” as if having been caught skinny dipping by his neighbors. This is a man in the throes of modernism. He has engorged himself on the excess pleasures of industrialization, gorged on jouissance!

Oh, Federico, what a laugh you must have had at the expense of this hideous bourgeoise. What Castellón sees in Poe is the futility of modernism. Men attempting to live as gods, a deliciously cruel joke, indeed. No matter how far we progress, no matter how much we create, no matter how new our ideas are, we are not gods. We will die. And by burying the possibility of transcendence beneath the tomb of history, we have destroyed the will to live. That’s what Nietzsche said, right? We must reclaim the will to power. Well, we never did, suggests the art of Castellón.

Castellón has been held in esteem by art historians as an important precursor to surrealism. What about you Federico, did you see yourself as a surrealist? “I was called a Surrealist without ever thinking that I was.” Surrealism, right? Only by turning towards the unconscious mind can we yield the utopia we strive towards. No, suggests Castellón, impossible.

Castellón wasn’t a surrealist, he was an anti-modernist. As a child, he witnessed the bloody limits of idealism. The chaos of anarchy. An explosive violence that could coexist alongside “progressive” thinking. Later, he would report being bullied and mistreated by the likes of Alexander Calder and the other modernist artists that hung out at Castellón’s prints dealer’s house. The radicals, Castellón saw, were just as spiteful, petty and narrowly careerist as the non-bohemians of the early 20th Century. No matter how hard modernists tried to birth the new — to do the work of the gods — they failed in evading the mask of red death. The modernist killed the mystic. Man killed the god. But man can’t be a god. And modernism can’t be mysticism.